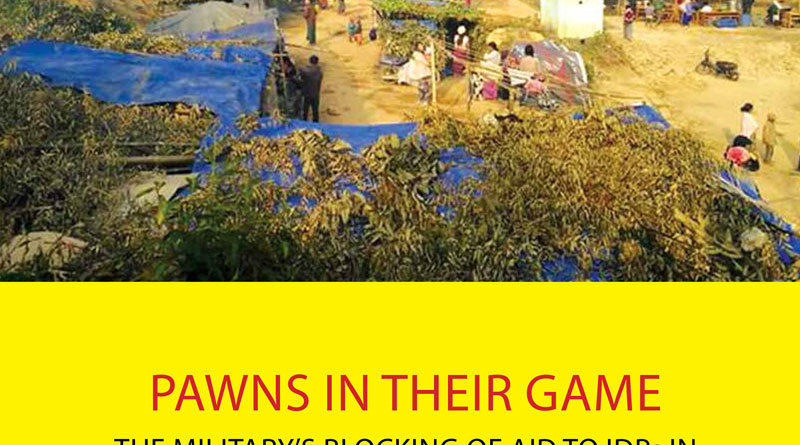

Pawns in their game: the military’s blocking of aid to IDPs in Kachin and northern Shan State

“They have received no aid since October and have barely any food left.They are trying to cook their tiny amounts of rice with rotten pumpkin leaves they find in the jungle.” Human rights activist Khon Ja describes the desperate conditions in non-government controlled Internally Displaced Person (IDP) camps in Kachin and northern Shan State in Burma/Myanmar, where the military has been blocking humanitarian aid deliveries since September 2014.

Some 98,000 civilians have been displaced since fighting re-ignited between the military and the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) in 2011, ending a 17-year cease fire. According to data collected by Kachin civil society organizations in October 2016, 29 IDP camps hosting 46,397 IDPs are in non-government controlled areas, with about half of inhabitants being children. An OCHA bulletin published on 19 December 2016 estimated that an extra 17,400 people has been displaced due to an intensification of fighting since then. Khon Ja estimates that around 65,000 IDPs are suffering from acute food shortages as a direct result of the military’s blocking of aid. This number includes around 1,000 individuals who escaped fighting in Shwegu and are now hiding in the jungle, not officially recognized as IDPs.

There has been widespread international condemnation. In October, Amnesty International’s Director for South East Asia and the Pacific, Rafendi Djamin, said that “All parties to the armed conflict have an obligation to allow and facilitate delivery of impartial humanitarian assistance for civilians in need. Blocking such aid is a violation of international humanitarian law.” On 1 December, several NGOs signed an urgent appeal to reinstate humanitarian aid to IDPs in Kachin and northern Shan State. The appeal noted that “IDPs have resorted to developing negative coping mechanisms, such as severely reducing food intake and taking on dangerous and high risk jobs, leading to migration and employment in unregulated and illegal activities.” On 12 December the U.S. embassy urged “immediate, unfettered humanitarian access to all those affected by conflict throughout the country.”

The military claim that they have blocked food deliveries as rations were going to the KIA and Bun Hkrang of the Kachin Baptist Convention’s Humanitarian and Development Department has said “We can do nothing if they [government officials] give security as the reason [for blocking deliveries]. This is the biggest challenge we face in delivering aid to KIA-controlled areas.” Koh Ja says that local aid organizations are unofficially managing to bring in small donations but that it is not enough.

Fighting between the military and the KIA intensified in the run-up to the 21st century Panglong peace conference, with the military launching artillery attacks against KIA posts near its Laiza headquarters on 18 August, less than two weeks before the Panglong peace conference. “KIA representative Lt Col Naw Bu commented “I think the Tatmadaw want to exert pressure on the KIA to sign the nationwide ceasefire agreement and to attend the political dialogue.” Seng Zin, general secretary of the Kachin Women’s Association of Thailand exile group has said that she is “concerned that refugees are being blocked from getting aid by the government in order to pressure the KIA into signing the national ceasefire.” According to Seng Zin, using humanitarian aid as a bargaining chip is a tactic that has been used in the military’s offensives against ethnic armed organizations frequently in the past. The United Nationalities Federal Council (UNFC), a coalition of seven ethnic armed groups (EAOs), claimed the army’s blocking of aid was part of a strategy of “Four Cuts” designed to vanquish the EAOs.

ND-Burma Coordinator, Han Gyi, commented “The Burma/Myanmar army has long used the blocking of humanitarian aid to the most vulnerable affected by the conflict as a tool to pressure ethnic nationalities to fall in line with their agenda. This cynical power play makes the trust necessary for national reconciliation and lasting peace impossible.”

Khon Ja says that the efforts of the Joint Strategy Team for Humanitarian Response in Kachin and Northern Shan State, a group made up of local humanitarian organizations, to lobby the Government to reinstate aid deliveries has received no response.

On the public level also, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and the NLD have met the ongoing violence in Kachin and Northern Sha State with silence. This is despite the fact that in Kachin the NLD won 22 out of 30 seats up for grabs in the 2015 election, giving the party a strong mandate to govern on behalf of the Kachin people. The ongoing violence and prolonged suffering of those denied humanitarian aid is damaging the faith the Kachin put into the NLD which subsequently endangers the peace process. Leader of the Maina KBC IDP camp in Waingmaw U Khw Taung, said: “We also voted for the NLD out of hope that they could bring good things for us. But they have no power. No one comes to us. We think they’ve forgotten us.”