Human rights report offers way forward to justice and healing

By FRONTIER

YANGON — Human rights violations spanning nearly 50 years have been detailed in a report that civil society groups say is a first step towards documenting abuses and seeking justice for victims.

You cannot ignore us: Victims of human rights violations in Burma from 1970-2017 outline their desire for justice,was released on October 16 by the Network for Human Rights Documentation Burma (ND-Burma), and its Reparations Working Group.

They hope the report will be an initial contribution to the establishment of a government-led reparations programme for victims of human rights abuses that will include acknowledging their suffering.

ND-Burma and its Reparations Working Group say the 94-page report, which examines 111 cases of human rights violations in 11 states and regions over 47 years, is the first such victim needs assessment to be conducted in Myanmar.

At the report’s launch in Yangon on Tuesday, 88 Generation leader U Ko Ko Gyi, explained how governments in other countries have promoted national reconciliation through laws supporting victims of human rights violations. “At least in Myanmar we should recognise what has been done,” he said.

The report’s publication comes 14 years after ND-Burma was founded by a group of activists to document human rights abuses so that victims and their families could seek justice after the country made the transition to democracy.

In 2015, ND-Burma, which has 13 members representing ethnic nationalities, women and former political prisoners, formed the Reparations Working Group to advocate for measures to help victims rebuild their lives. The group comprises all ND-Burma members as well as other civil society groups that seek justice for victims of abuses.

Of the 111 cases detailed in the report, 85 were victims of conflict, 13 were land grab victims and 13 have been political prisoners. In 95 cases (85 percent), the violations involved the Tatmadaw and other government security forces, 13 involved armed ethnic groups and the rest, unknown perpetrators.

In almost every case, victims said their lives had been negatively affected, whether physically, psychologically, socially or economically, or a combination of all four. They overwhelmingly wanted some form of action from the government or perpetrators to try and alleviate the impact of the abuses they had suffered.

San Hoi, a secretary of the Kachin Women’s Association-Thailand, talked on Tuesday about the lasting impact of the country’s civil conflicts on people in ethnic areas. Those who have suffered abuse receive little government support and are instead left to find their own solutions, she said, but “There are things the government can do, such as taking care of health, education and protection”.

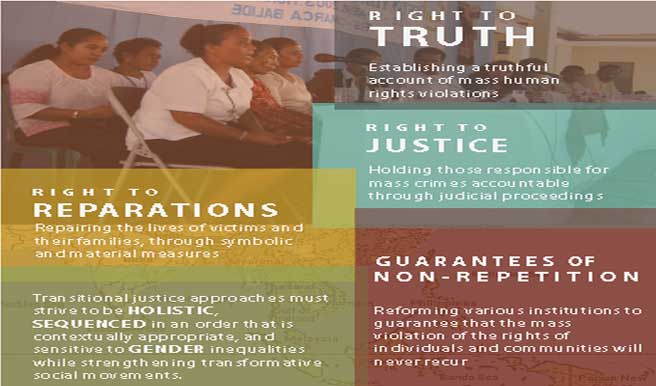

The report said the most common desire for justice was institutional change to guard against human rights violations occurring again. Victims also asked for some form of symbolic satisfaction to make them feel as if they had received justice, as well as for compensation, and for restitution – of land, property, the release of a wrongly imprisoned relative or restoration of civil and political rights.

It said many victims had wanted justice but had little confidence that it could be delivered through the legal system.

The report says that with Myanmar under its first democratically-elected civilian-led government in more than 50 years, the time for justice has arrived.

“So far the conversation on transitional justice – the ways in which a country emerges from and addresses periods of mass human rights violations – has been limited to domestic civil society, with most elites refusing to publicly discuss redress for victims,” the report says.

“Yet transitional justice is not about ‘retribution’. It is about acknowledging that people’s human rights have been violated and that they deserve redress. It is about establishing the facts of what happened and reforming institutions to ensure it never happens again. It is about ensuring access to justice and respect for the rule of law. And it is about rebuilding trust throughout society to bring about reconciliation and lasting peace.”

The report said decades of military dictatorship and civil war have meant that there was a poor understanding of human rights and fundamental freedoms throughout society.

Victims also often do not have the language to speak about human rights following decades, often lifetimes of repression.

“Our work aims to help survivors of human rights violations articulate what assistance they may need to rebuild their lives,” the report says.

It says the needs assessment shows that victims’ demands for justice are relatively modest and urges the government “to take advantage of this to kick-start a truly ‘national’ reconciliation process”.

It quotes political analyst U Win Zin as saying, “In order for national reconciliation to work it has to be systematic. So far there has been no reconciliation between the military and the people.”

The report says victims of human rights violations deserve to see justice for what they have suffered.

“In order to end ongoing human rights abuses the rule of law needs to be respected and impunity for violations brought to and end through judicial reform,” it says.

“However, ND-Burma’s needs assessment shows that victims have very immediate needs that the government has the responsibility to address. The findings of this report and ND-Burma’s 14 years’ experience of documenting human rights violations first-hand show that Burma urgently needs a wide-ranging reparations programme to help victims repair their lives and kick-start a real national reconciliation.”

The report’s recommendations include the enactment of a Reparations Law that acknowledges mass human rights violations have been committed and that victims require reparations through a government programme.

It also recommends that the issue of reparations be included in the 21st Century Panglong Union peace conferences and that discussion be broadened to include all victims of human rights abuses, and not only those displaced by conflict.

Other recommendations call on the government to grant humanitarian groups, human rights monitors and the media unfettered access to areas where there had been allegations human rights abuses and to end the surveillance and harassment of field workers documenting violations.

The report recommends the adoption of a military code of conduct that meets international human rights standards and that soldiers accused of abuses be prosecuted in civilian and not military courts.

It also recommends the abolition of article 445 from the 2008 Constitution, which grants immunity to members of previous military governments.

Other recommendations call on the government to ratify the UN Convention Against Torture and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and to revise the National Human Rights Institution Law in line with the Paris Principles so the Myanmar National Human Rights Commission can be reformed to become truly independence and effective.

It also calls for school textbooks to be revised in consultation with ethnic nationality communities to reflect their history and provide an uncensored account of past abuses.

The report features a quote from surgeon, writer, activist and former political prisoner, Ma Thida (Sanchaung), “The most important thing is acknowledgement of people’s suffering. If we don’t identify the wound, how can we heal it?”