‘Don’t open the door’: Junta’s midnight raids arouse fear and resistance

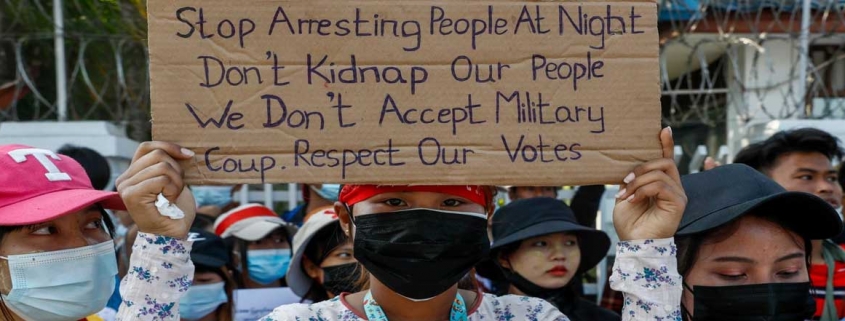

A long-expected crackdown on the protest movement is gaining pace but late-night raids to arrest suspects are meeting noisy resistance from citizens.

By FRONTIER

It has become a sad ritual of life in post-coup Myanmar: scanning Facebook each night for reports – even livestreams – of the latest arrest of an activist or dissenting civil servant.

Grainy videos show armed military and police officers in the dark of night urging suspects to leave their homes, using a phrase – “kanar lite ke par”, or “please come with us for a moment” – that has historically been associated with arrests of dissidents.

With hundreds of thousands of people joining mass protests throughout the country and increasing numbers of civil servants leaving their desks as part of a Civil Disobedience Movement, the military has embarked on a spree of arrests aimed at suppressing opposition to its February 1 takeover.

As of February 15, at least 426 people had been arrested or detained for political activities since the coup, the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, which was formed by activists in 2000, told Frontier. This includes members of the National League for Democracy and officials of the Union Election Commission and its sub-commissions. Three people have so far been sentenced, while 35 have been released.

Not only are large numbers of people being arrested, but AAPP member U Tun Kyi said that in many cases authorities are not giving any reason for their detention. It’s not clear where many of the detainees are being held, and they are not yet appearing in court or being granted access to lawyers.

“We do not have figures for the exact number of arrests, but we calculate that there are about 200 officials from the government, the NLD and the election commission, and nearly 100 civilians have been arrested since the protests started,” Tun Kyi told Frontier on February 12.

Most of those arrested are doctors who support the civil disobedience campaign and young activists involved in street protests.

There are fears the number in detention could rise significantly, particularly after the junta amended the Penal Code on February 14 to broaden the definitions of sedition, incitement and high treason, and in some cases also increase the penalties.

‘My children are asking for their father’

When four plainclothes police came to arrest Dr Pyae Phyo Naing at around noon on February 11, the 38-year-old head of Ingapu Township Hospital was treating a patient at a charity clinic.

“My husband asked if he could finish suturing a patient’s head wound,” recalled his wife, Dr Phyu Lae Thu. “But they wouldn’t wait and summoned another five police in uniforms who used force to push him into their car. When we tried to pull my husband away from them, they pointed their guns at us.”

Phyu Lae Thu told Frontier on February 12 she was certain her husband was detained for leading the CDM at the hospital in Ingapu.

“They [the police] did not give their names or their ranks or the reason why they wanted to take my husband. They only said they wanted to talk to my husband and he would be gone for a while,” she said.

Pyae Phyo Naing is an asthmatic and has a heart condition for which he needs to take medicine regularly. Phyu Lae Thu said she still does not know where he is being detained or when he will be released, but insisted her husband’s rights had been violated.

“He was not at the police station when I went there yesterday with clothes and medicine, which they said would be sent to my husband. Some witnesses say my husband was taken to a Tatmadaw base near Kwin Kauk,” she said.

The couple have two children, aged five and ten. “My children are asking for their father,” said Phyu Lae Thu, bursting into tears.

On February 16 she told Frontier she had learned her husband was in Hinthada Prison, but she had no information on his condition and neither she nor a lawyer had been able to meet him.

But Pyae Phyo Naing is not the only doctor to be detained at gunpoint. A video that spread on social media on February 11 showed U Win Hlaing, a member of the Myittar Shin Funeral Charity Association in Nansang being arrested by more than 10 soldiers. Win Hlaing had been playing a leading role in protests in the Shan State town. The soldiers who took him away refused to say why he was being arrested or where he was being taken.

Tun Kyi from the AAPP said that under the law, the police cannot detain a person for more than 24 hours without a court order. Police arrests since February 1 have involved clear violations of the law, he said.

He said the situation was similar to in the 1990s, when it was common for activists to be detained at nighttime.

Foiling arrests

But police have not always been successful. In the Sagaing Region capital, Monywa, two men in plainclothes tried to detain Ko Zaw Thurein Tun, chair of the Sagaing Township Computer Industry Association, at his home on February 10.

Zaw Thurein Tun released CCTV footage of the encounter that shows him using his mobile phone outside his home when he is approached by two men who try to seize him. When Zaw Thurein Tun resists and family members emerge from the house, three policemen join the attempt to arrest him. Neighbours gather and the police and the men in plainclothes back off. Zaw Thurein Tun has since gone into hiding.

“They did not say why they wanted to arrest me,” he told Frontier. “But I think it is because I was always at the front of the protests in Monywa.”

Citizens are also finding other ways to foil the police, including by livestreaming their attempts to arrest people in midnight raids in order to mobilise neighbours to prevent them from apprehending their target.

One such incident occurred in Mandalay about midnight on February 11 when police tried to arrest the rector of the University of Medicine (Mandalay), Professor Khin Maung Lwin.

Witnesses said about four police entered the family compound by scaling a fence “like thieves”.

The rector’s daughter raised the alarm by livestreaming the raid on Facebook. Within minutes, the police found themselves surrounded by hundreds of residents and retreated, empty-handed.

In many towns and cities, but especially Yangon and Mandalay, residents have been successful in foiling arrests by livestreaming raids on social media or banging pots and pans to raise the alarm when suspicious people or vehicles are spotted in their neighbourhoods.

There’s concern in the protest movement that the junta may shut down the internet in order to prevent arrests from being livestreamed, or that the State Administration Council will enact a recently released draft of the Cyber Security Law, which would put anyone using social media for anti-government purposes at risk of arrest.

The SAC has already undertaken a suite of legal changes to erode citizens’ rights and make it easier to arrest and imprison them for dissent.

It has reinstituted a section of the Ward and Village Tract Administration Law requiring all overnight guests to be registered, which in the past police often used as a justification to conduct “midnight inspections” without a warrant, making it easier to carry out arrests.

The regime on February 14 also enacted a range of amendments and additions to the Penal Code and Code of Criminal Procedure, including broadening the definitions of high treason, sedition and incitement, and in some cases increasing the penalties.

On February 13, it also suspended three sections of the Law Protecting the Privacy and Security of Citizens, including the requirement that witnesses be present when a search is conducted, and a prohibition on authorities entering private property to conduct searches, seize evidence or make arrests without a warrant. Another suspended section required a court order to detain suspects for more than 24 hours.

A knock on the door

The authorities came for astrologer Lynn Nyo Tar Yar, 26, at his family home in Yangon’s South Okkalapa Township at 11pm on February 11, apparently because of his alleged sorcery against the military government.

Lynn Nyo Tar Yar, who has a wide following online, had posted on his Facebook page images of nine blades laid in a specific arrangement with burning candles on them – part of a ritual he said would “destroy the dictators”.

His father, U Tun Htut, told Frontier that five people, including two uniformed policemen, came to their home.

“We said if they want to arrest him, they should return after 4am when the curfew is lifted, but they threatened us all with arrest if we didn’t open the door. When we opened it, they put my son in a car and drove away,” he said.

Livestream footage of the encounter shows two men in plainclothes rudely ordering the door to be opened. One of them says, “It’s none of your business what time we come to make arrests – whether it’s day or night. We are here in line with the law.” He did not say which laws.

The livestream coverage alerted neighbours, who came out of their homes in their dozens and followed the police cars. About 200 neighbours marched to the township police station, where they remained until after curfew the following night. At 9pm on February 12 the crowd was still 300 strong, with some holding candles, but Lynn Nyo Tar Yar remains in custody.

It has emerged that the General Administration Department filed a complaint against Lynn Nyo Tar Yar under section 505(b) of the Penal Code for “making, publishing or circulating any statement, rumour or report likely to cause fear and alarm in the public that may induce any person to commit an offence against the State or against public tranquility.”

Tun Htut said his son has a heart ailment and there is an oxygen tank “ready for him at home”. He said he had taken necessities to the police station for his son on the morning of February 12. “I had a chance to see him; his condition so far is good,” he said.

Legal consultant U Khin Maung Myint said that even with the suspension of sections of the Law Protecting the Privacy and Security of Citizens, arresting officers are still required to show an order signed by either a court or the head of a police station, and the arrestee has the right to ask who brought charges against them and why.

“If the police cannot answer, people can reject the arrest. Don’t open the door. If you open the door, they will arrest you by force,” he told Frontier. “If the police abuse their power by arresting people by force or not saying where detainees are being held, the people have the right to counter charge them.”

“Of course, it depends on the police whether they will follow the law or not, or even whether they understand it. If they don’t, the people will continue to suffer,” he added.

But U Aung Myo Min, founder of Equality Myanmar, a civil society group, said justice could not be expected from police and prosecutors under the SAC. The people need to be able to protect each other from police abuses, he said.

“At the moment, we can only keep records of abuses by the authorities, because there is no person or organisation to which we can complain,” he said. “All we can do is show to the world what is happening. The police in Myanmar are behaving like terrorists in police uniforms.”