Harvard war crimes report puts spotlight on transitional justice

Paul Vrieze, Yangon, International Justice Tribune, No 171, 3 December, 2014

A recent independent report finds three senior military officers could be held responsible for war crimes and crimes against humanity allegedly committed by Myanmar army personnel during an offensive against ethnic armed groups in the east of the country.

Last month, the International Human Rights Clinic at the Harvard School of Law published a legal memorandum finding sufficient evidence to satisfy the standards set by the International Criminal Court (ICC). The report named the three officers, including current home affairs minister Major-General Ko Ko.

The army’s counterinsurgency policies occurred during a 2005-2008 offensive targeting the ethnic civilian population. Some 42,000 ethnic Karen were displaced in an effort to deprive rebels of support.

Lead researcher Matthew Bugher explained to IJT that the report was published to “help facilitate conversations about Myanmar’s past and on-going human rights abuses”, while also warning current army commanders that “they too could be held responsible for abuses”.

The report raises difficult questions about whether the country can begin the process of transitional justice to address and end rights abuses. Myanmar, formerly known as Burma, is in the fourth year of a democratic transition away from decades of brutal military rule and ethnic conflict. Successive military regimes have imprisoned, tortured and killed thousands of political activists. Hundreds of thousands of civilians were killed, displaced or suffered abuses by the army during a decades-long civil war against armed groups seeking autonomy for oppressed ethnic minorities.

Prosecution far off

Tomás Ojea Quintana, who was the UN special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar until April, believes the Harvard report offers an unprecedented amount of detailed evidence on military crimes during ethnic conflict. But, he says, successful prosecution in Myanmar is unlikely soon due to the remaining political powers of the old elite and the army. A constitutional clause grants immunity for crimes committed under the former regime. Plus, the civilian court system lacks independence from the government, while the military retains its own system to adjudicate in cases involving soldiers.

“The National Human Rights Commission told me they don’t have the mandate to address abuses by the army – it’s a reaction you get from all authorities regarding accountability,” Quintana told IJT. “The military is still in power to a large extent and so long as that is the case, such [legal] actions are very difficult.”

Bugher said he was encouraged that Myanmar’s defence minister agreed to meet him to discuss the report, although the official had dismissed the findings as “one-sided and inaccurate”.

National ceasefire negotiations in recent years have hit a deadlock and conflict continues in northern Myanmar. That said, the process has so far skirted the issue of transitional justice, according to Quintana, and plans for a truth commission dealing with the conflict have not been broached.

Non-judicial ways to address rights abuses, such as commemorations of episodes of abuse and repression, are only just beginning and limited to a few civil society organization initiatives, Quintana explained. “In Myanmar, the society, the people, have not really developed a discussion on this issue [transitional justice] and how to move forward,” he said.

Human rights on the agenda

Although opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) holds several seats in parliament, opposition lawmakers and many activists are reluctant to start public discussions. They fear that could cause the army and the ruling party to stymie the transition.

“Suu Kyi told me she doesn’t believe in revenge and finger-pointing, but she said for those who suffered human rights abuses there should measures taken to help them heal, perhaps through reparations – but then we haven’t seen any steps towards this,” Quintana said. If the NLD makes major parliamentary gains in next year’s election, as promised by the former juntaturned-civilian government, “there will be an opportunity to put human rights and transitional justice on the agenda”, he said. Long-term success of Myanmar’s democratic reforms requires steps to address past abuses, Quintana stressed.

Though reluctant to discuss possible prosecution of former regime members, NLD spokesman Nyan Win said: “To satisfy the citizens of Burma, we need a truth commission, like in South Africa. We have always said this – but at the time of a purely civilian government, not during this government. After next year’s election, we’ll have to look at this.”

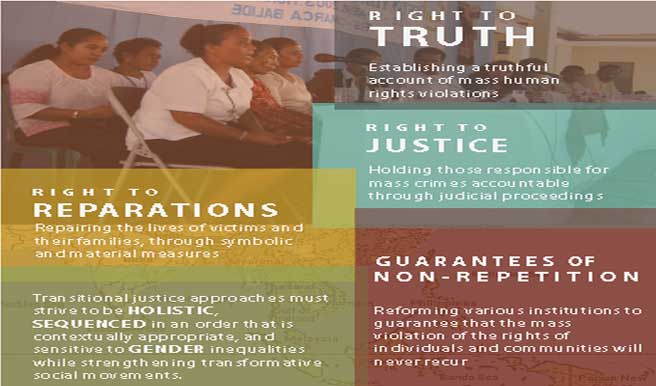

According to Aileen Thomson, the International Center for Transitional Justice’s representative in Myanmar, “The challenge is that in this context, many people understand ‘transitional justice’ to mean criminal prosecutions motivated by revenge, and this is understandably not appealing. However, transitional justice is not about revenge, and not limited to prosecutions.”

The Network for Human Rights Documentation-Burma – like many rights organizations, based in Thailand bacause it cannot work openly in Myanmar – has begun with non-judicial ways to address rights abuses, such as truth-telling and commemoration, which help victims and make information about abuses available for public discussion.

“These events are actually not allowed and organizers face some challenges and threats from police. It’s not easy, but people are trying to do this,” coordinator Han Min Soe said. His network has so far organized four truth-telling events for ex-political prisoners and victims of ethnic conflict, he said, adding that authorities actively blocked former regime officials from participating.

But some perpetrators want to confess, he noted. “They also feel like … victims because they feel guilty, but they cannot tell their stories to others.”