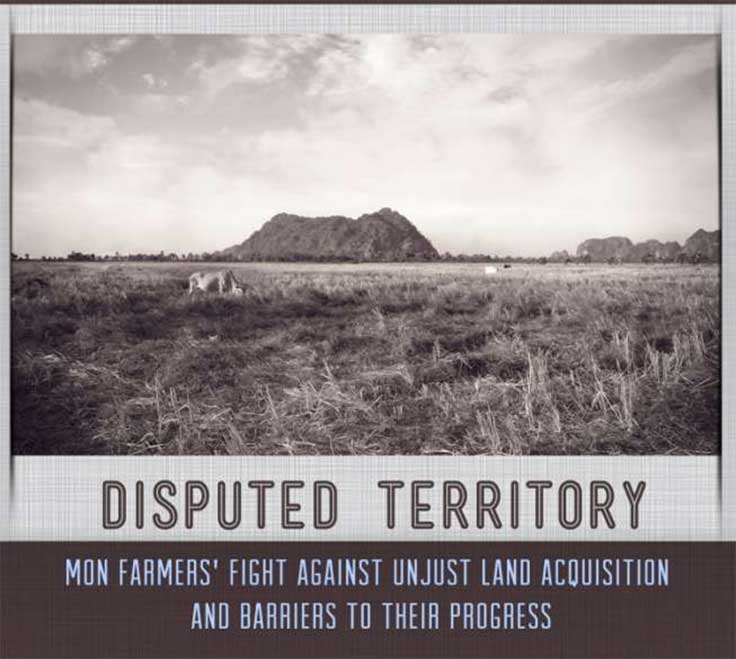

Disputed Territory: Mon Farmers’ Fight Against Unjust Land Acquisition And Barriers To Their Progress

A. Introduction

Over the years HURFOM has produced a number of accounts highlighting the hardships faced by Mon farmers who became victims of land confiscation or unjust land acquisition.[1] In this report HURFOM follows-up on previously documented abuses and concentrates on an emerging new trend: farmers’ active and collective pursuits for rights to their land.HERE

Disputed Territory aims to elaborate on the activities of and express solidarity with farmers who are resolutely, and in some cases for the first time, seeking justice regarding their land. To exhibit current challenges and bring into focus some of the key obstacles in the Mon context, this report uses case studies of appeals over past military land confiscations in Ye Township and on-going transgressions by various investors in Kyaikmayaw Township. Where barriers to justice exist, HURFOM recommends effective and immediate solutions.

HURFOM contends that farmers’ newly voiced demands present an important opportunity for President Thein Sein’s government. Inherent in an environment of growing activism is the chance to meet appeals with justice, thereby demonstrating to domestic and international critics that the administration is committed to a clear break with the abuses of past military regimes. Violations of farmers’ rights need to be publicly condemned and owners of wrongfully seized land must have property restored or be given fair compensation. There is an urgent need for the establishment of a credible legal framework to prevent dispossession and violated rights from continuing to be hallmarks of agrarian life under this government’s nominally civilian rule.

The argument presented herein is simple. Since 2011 farmers have been actively pursuing their rights to land, yet to date little progress has been made. Few past victims of unjust land acquisition have had land returned, misconduct by investors in land acquisition continues, and secure land rights remain virtually absent from Burmese law.

Given the focus on farmers’ struggle for their rights, this report pays considerable attention to the legal framework in which past and on-going land disputes have taken place. Inadequate legislation and public lack of awareness of existing legal rights are highlighted as key reasons why Mon farmers do not possess rights to their land in 2013. In a nation emerging from conflict and actively pursuing economic development, farmers are in desperate need of robust, legally enshrined protection of their land rights.

Given the focus on farmers’ struggle for their rights, this report pays considerable attention to the legal framework in which past and on-going land disputes have taken place. Inadequate legislation and public lack of awareness of existing legal rights are highlighted as key reasons why Mon farmers do not possess rights to their land in 2013. In a nation emerging from conflict and actively pursuing economic development, farmers are in desperate need of robust, legally enshrined protection of their land rights.

With government land surveys characterised by a lack of transparency and enduring bias, the precise number of acres of land unjustly acquired from Mon farmers over the years remains nearly impossible for an organisation of HURFOM’s capacity to confirm. However, information gathered for this report suggests that it stretches to tens of thousands of acres. HURFOM calls on all persons in positions of authority to elevate the voices and champion the rights of farmers who for generations have crafted Burma’s unique and prolific landscape.

B. Methodology

| S |

ince 1995 HURFOM has been engaged in documenting the voices of Mon populations with research methodology that was developed over these 18 years of experience.

Research for this report was conducted from April to September 2013. During this period five field reporters visited four Mon-populated townships: Mon State’s Ye, Thanbyuzayat and Kyaikmayaw townships, and Tenasserim Region’s Yebyu Township. Interviews were conducted in person where possible and by phone when transport or security issues made interviewees’ locations inaccessible, and field reporters shared interview transcripts and field notes with HURFOM via satellite phones and online communications. With local authorities often backing the military personnel and companies involved in cases under investigation, field reporters noted they had to carry out research with caution.

After preliminary visits it was decided that field reporters would focus on Ye and Kyaikmayaw townships because cases there reflected the spectrum of different perpetrators against whom Mon farmers are appealing unjust land acquisition: military in the former and various companies in the latter. Ye and Kyaikmayaw were also determined to be better suited to collecting comprehensive data than other regions; in Thanbyuzayat and Yebyu townships victims of confiscation had more consistently migrated to neighbouring countries for work opportunities.

Field reporters made use of an extensive network to facilitate interviews and gain the confidence of victims. On our reporters’ fourth and final trip to Ye Township, a local religious leader provided assistance that was invaluable to our work.

In total close to 100 interviews were conducted. 83 local residents were consulted in Ye and Kyaikmayaw townships and seven in Yebyu Township. In Ye Township 14 villages were covered, whilst testimony was obtained from residents of five Kyaikmayaw villages. In addition, field reporters consulted four members of the Settlement and Land Records Department, two parliamentary representatives (both members of the Land Investigation Commission), five members of village administration, one Union leader and numerous legal experts. Where possible HURFOM uses the real names of interviewees, although many requested to remain anonymous or to appear under an alias given security concerns related to their cases. Similarly, for protection of interviewees and at their request, in some cases their precise locations are not listed.

Over the course of this research, various persons declined to talk with HURFOM reporters. Some victims of military confiscations in Ye Township expressed distrust for our reporters, saying they would only cooperate with political parties. Of 12 civil servants who declined interviews, two said they were concerned about farmers’ rights in on-gong land disputes but feared that giving testimony might jeopardise their positions. All companies active in Kyaikmayaw Township refused requests for information.

In addition to conducting interviews, HURFOM was able to obtain copies of correspondence regarding land disputes in Ye, Kyaikmayaw, Yebyu, and Thanbyuzayat townships. These contained both original letters of appeal from residents and responses by government personnel.

Where possible, cases represented here are given in the fullest and most accurate detail possible, with hopes that the information gathered in this report may be used as an advocacy tool for advancing the cases of the victims. Appendix 2 contains a list of confirmed cases of military land confiscation in Ye Township, all of which remain unresolved. This register was made by crosschecking a list of victims in Ye compiled from HURFOM’s archives with new information obtained during this year’s interviews. Whilst the original list was too extensive for all cases to be followed up directly during our data collection period, in each village reporters invited a handful of interviewees to the local monastery to discuss their and others’ cases.

Attempts to confirm cases in Ye revealed to HURFOM the challenges faced by agents investigating land disputes. In some villages it was difficult for reporters to accurately track the chronology of land ownership due to sale, rental or re-confiscation of land. It was also noted that land acreage and the number of agricultural assets (trees or plants) involved in confiscations proved difficult to confirm due to falsified military records, deficient land documentation, inflated claims by victims hoping to secure more compensation, and human error when remembering exact circumstances.

Attempts to confirm cases in Ye revealed to HURFOM the challenges faced by agents investigating land disputes. In some villages it was difficult for reporters to accurately track the chronology of land ownership due to sale, rental or re-confiscation of land. It was also noted that land acreage and the number of agricultural assets (trees or plants) involved in confiscations proved difficult to confirm due to falsified military records, deficient land documentation, inflated claims by victims hoping to secure more compensation, and human error when remembering exact circumstances.

In addition to new materials collected, this report includes information, testimonies and images from HURFOM’s extensive archives. It also draws on the growing number of news articles and research documents available surrounding land conflict and rights in Burma, supplemented by original pieces of land rights legislation. As far as possible, HURFOM aimed to analyse research collected in Mon regions in the context of wider land rights issues throughout Burma.

C. Background

1. Land confiscation under military rule: 1962-2011

| L |

and confiscations under military rule were supported by a domestic legal framework that flouted international norms (see Appendix 1) and in which land could be seized from owners within the parameters of the law.[2] By the time Ne Win’s military government took power in 1962 legally defined land rights in Burma, also known as Myanmar, had seen significant decline. British colonial rule had recognised private ownership of land and, whilst land could legally be acquired by the State for public purposes, in this period landowners enjoyed various rights over the use and transfer of their land.[3] However, when Burma gained independence from British rule and moved to a model of socialist governance, private land rights were replaced by a system in which the State formally owned and could exert claims over the country’s land.

The 1947 Constitution, adopted immediately prior to 1948 independence from British colonial rule, formally designated the State as the ultimate owner of all land.[4] This was followed by the 1953 Land Nationalisation Actthat, with the exception of smaller plots of land (up to 50 acres) that farmers could prove they had owned since 1948, brought all agricultural land subject to State reclamation and redistribution schemes.[5] The aim of this legislation was to protect smallholder farming and reverse large-scale acquisitions that had taken place in the post-independence period, but it set a precedent for the State wielding constitutionally defined ownership rights and legally seizing land. Even before the 1962 military coup the way was paved for widespread land confiscation.

With a legal basis for land confiscation already in place, successive military governments reaffirmed, enhanced, and increasingly exercised the State’s legal ownership of the country’s land. Shortly after Ne Win seized power the 1963 Disposal of Tenancies Act was passed, deepening State control over land by establishing the State’s right to terminate landlords’ tenancy arrangements and initiate its own.[6] Furthermore, both the 1974 and 2008 Constitutions reiterated that the State was the ultimate owner of all land.[7] As military demands for land arose and confiscations proliferated, the justification that the State was acting in accordance with rights conferred to it by the country’s law was repeatedly employed.

(i) Land confiscation by military battalions

One of the most prominent types of land confiscation in Mon areas under military rule was the seizure of civilian land by military battalions. Where compensation was paid it was described as negligible, and most victims reported receiving none at all.[8]

In Mon regions land confiscation by the military is recorded as most prolific after 1995. Prior to that year the regime was still waging war against a number of the country’s ethnic minority populations and large regions of Mon territory were held under the direct control of the New Mon State Party (NMSP), the predominant ethnic Mon resistance group. However, the 1995 ceasefire between the NMSP and Burmese military forces returned many of these areas to governmental administration. As the military sought to exert its control and counter renewed insurgencies, increasing numbers of troops were deployed to this newly accessible territory.[9] These battalions began to build bases, often employing forcible confiscation to meet their growing land needs.

To make matters worse, in 1997 government funding for military activities was severely depleted and battalions were ordered to follow a policy of ‘self-reliance’. Battalions’ demands for land outgrew just housing and acreage for bases to include the need for farming projects that supplied food and income to cover operating costs. As the rising number of military units based in Mon areas attempted to better meet their own needs, land confiscations gathered pace.[10]

Troop deployments to Mon areas and resulting land confiscations further intensified when preparations began in 1998 for the construction of the government-owned Kanbauk to Myaing Kalay pipeline. Running from Tenasserim Region to Karen State, the 183-mile-long pipeline was to travel the length of Mon State through five different townships.[11] With military forces tasked with its construction, security and maintenance, by 2003 over 20 new battalions had been deployed along the pipeline’s route.[12] In a report published in 2009, HURFOM stated that pipeline battalions had seized approximately 12,000 acres of land in addition to the 2,400 acres confiscated by the State to clear a path for the project.[13]

A large number of these land confiscation cases were concentrated in Mon State’s Ye Township and are detailed in Section E.

(ii) Land confiscation by local administration

In addition to land acquisition by battalions, under military rule Mon farmers routinely experienced land confiscation by village administrators. In some cases this was carried out in response to orders from above dictating confiscation on behalf of the military or for State projects, but on other occasions administrators took advantage of the government’s tolerance of local-level corruption and seized land for personal gain.

In addition to land acquisition by battalions, under military rule Mon farmers routinely experienced land confiscation by village administrators. In some cases this was carried out in response to orders from above dictating confiscation on behalf of the military or for State projects, but on other occasions administrators took advantage of the government’s tolerance of local-level corruption and seized land for personal gain.

Since 2011 when political and civil space began to open for farmers to lodge appeals regarding military-era confiscations, new cases have come to light (see Section D). For example, from 2011-12 farmers from Thanbyuzayat Township sent two successive letters of appeal to State authorities detailing confiscations in their home village of Kayokepi in 2008. The letters alleged that the village’s administrator, U Cartoon, had seized 19 acres of land from five farmers, splitting it into small plots and selling it for profit.[14]

An investigation in 2011 by the Thanbyuzayat Township General Administration Department concluded that the Kayokepi land had been confiscated following orders from a Light Infantry Battalion (LIB) General and that its sale was intended to raise funds for the construction of a road between Kayokepi and Htin Shu villages. The road was indeed subsequently built, but U Cartoon has since proved unable to provide a detailed account of how the money was spent.[15] Whether or not the funds were wholly used for the road’s construction, the case demonstrates the common theme of a lack of transparency.

Similarly, HURFOM documented this year that 201 acres of land were allegedly confiscated in late February 2011 from residents of Kaloh village in Ye Township by sub-Township Administrator U Kyaw Moe and village administrative staff. Like the Thanbyuzayat case, land was split into small plots and sold off. Villagers were told that the resulting profit would be invested in community development, but they allege this promise never materialized in any visible way. Given the lack of transparency, residents were left to assume that village administrators personally profited from the sale.[16]

2. Continuing land conflict under civilian government: 2011-13

Despite the inauguration of a nominally civilian government in March 2011, unjust land acquisition has remained a recurring theme for Burma’s rural and agrarian populations. Almost a quarter of the human rights violations recorded by the Network for Human Rights Documentation – Burma (ND-Burma) from April to September 2012 consisted of land confiscation cases that reached across seven different states[17] and the group called land confiscation “one of the most pressing issues of 2012”.[18]

(i) Continued abuses by the military

Since 2011 reports have continued to emerge of military land confiscations in Mon regions. In June 2011 HURFOM reported on land confiscations by Navy Unit No. 43 on Kywe Thone Nyi Ma Island in Tenasserim Region’s Yebyu Township.[19] Although confiscations began in December 2010 prior to Thein Sein’s presidency, they continued into the new government’s term.

Since 2011 reports have continued to emerge of military land confiscations in Mon regions. In June 2011 HURFOM reported on land confiscations by Navy Unit No. 43 on Kywe Thone Nyi Ma Island in Tenasserim Region’s Yebyu Township.[19] Although confiscations began in December 2010 prior to Thein Sein’s presidency, they continued into the new government’s term.

At the time of the 2011 report 1,000 acres of land had already been seized, reportedly with no compensation paid, and a further 3,000 acres of land were designated for acquisition by the navy unit.[20] A communication from Secretary Myo Aung Htay on behalf of the President in August 2011 detailed that 81,196.62 acres of land in the area had been transferred to the navy unit.[21] Although the letter held that at the time of seizure none of the land was being cultivated or used and was therefore rightfully acquired, testimonies collected by HURFOM earlier that year disprove this claim and suggest that at least some portion was unjustly confiscated from residents.

(ii) Peace process land acquisition

With President Thein Sein’s administration heralding its emphasis on democratic reform, one of its central priorities since 2011 has been an end to conflict between Burmese military forces and the country’s numerous ethnic armed groups. However, over the course of negotiations reports have emerged of farmers becoming unwitting victims of the peace process. Allegedly, in some cases land has been used as a bargaining tool to appease armed groups or as a means to incite division between the ethnic populations they represent.

With President Thein Sein’s administration heralding its emphasis on democratic reform, one of its central priorities since 2011 has been an end to conflict between Burmese military forces and the country’s numerous ethnic armed groups. However, over the course of negotiations reports have emerged of farmers becoming unwitting victims of the peace process. Allegedly, in some cases land has been used as a bargaining tool to appease armed groups or as a means to incite division between the ethnic populations they represent.

In May 2013 residents from 14 villages in Paung Township of Mon State protested against on-going injustices in their communities. [22] One major complaint surrounded a conflict over 3,000 acres of land in Zin village marked for confiscation by the NMSP to be used in an NMSP agricultural project. Nai Tala Nyi, an NMSP representative, detailed that since 2004 the group had sought permission from the government to appropriate this land. The permission was finally granted when the NMSP signed a ceasefire with the government in 2012.[23] Whilst the NMSP stated that no land would be confiscated if farmers could prove ownership and that around half of the chosen land was too mountainous to be cultivated, the case highlights the impact of negotiations between government and ethnic actors on farmers’ land security.

With numerous armed factions operating in Mon areas, the NMSP has not been the only group involved in land conflicts during the recent peace process. In July 2013 HURFOM published a case study detailing land confiscated in Kha Yone Guu of Kyaikmayaw Township by the Mon Peace Process group, also known as the Nai Syoun group, which is a breakaway from the NMSP.[24] Having allegedly built good relations with the Burmese military by selling them illegally imported arms, in 2012 the group was granted permission to deploy troops to Kha Yone Guu and immediately sought land to build a base. Cases of confiscation reportedly included villagers who could present ownership papers for their land and residents who were threatened at gunpoint or otherwise intimidated into handing over high value land for minimal compensation. One Kha Yone Guu resident expressed his belief that the government had permitted the confiscations to turn Kha Yone Guu’s Mon residents against the armed group.

“It is a kind of strategy of the government in its military policy to create conflict within ethnic groups. So the government creates opportunities for armed groups to carry out such activities.”[25]

(iii) Land conflict linked to economic development

In addition to curbing ethnic conflict, another stated priority of President Thein Sein’s administration has been to significantly advance Burma’s economy. However, it is of concern to HURFOM that pursuit of this goal appears to have generated a wave of unjust land acquisitions throughout the country, including in Mon populated areas.

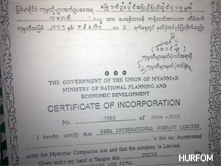

Several land conflicts occurring after 2011 reportedly involved misconduct by domestic and foreign investors as they scramble to acquire vast tracts of land for development projects. For the most part this is not a new trend; since the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) moved away from Socialism in 1988 and towards a market economy, disputes over companies’ land acquisitions have routinely arisen.[26] The 1991 ‘Wasteland Instructions Law’ that sanctioned granting companies up to 5,000 acres of terrain classified as ‘wasteland’ for leases of up to 30 years, in many ways opened the door for this. However, since 2011 such cases have been occurring at a rapid rate. Land prices in Burma are soaring and show no immediate signs of reversal, and investors have attempted to grab plots of land while they can at a comparatively low expense. For foreign investors, the 2010 elections and subsequent relaxation of Western economic sanctions provided the impetus to initiate projects within an emerging economy. Later sections of this report detail how 2012 laws privileged new investors’ interests, leaving farmers’ land rights largely unprotected in the process.

High profile cases such as disputes over the China-backed Letpadaung copper mine project are among the most visible symptoms of an emerging land acquisition epidemic to which Burma’s ethnic regions are not immune.[27] Reportedly, farmers in ethnic border areas are at some of the highest risk of unjust land acquisition by new investors. A report by the Transnational Institute and Burma Centre Netherlands states:

High profile cases such as disputes over the China-backed Letpadaung copper mine project are among the most visible symptoms of an emerging land acquisition epidemic to which Burma’s ethnic regions are not immune.[27] Reportedly, farmers in ethnic border areas are at some of the highest risk of unjust land acquisition by new investors. A report by the Transnational Institute and Burma Centre Netherlands states:

“Burma’s borderlands are where regional cross-border infrastructure and millennium-old trade networks converge and are some of the last remaining resource-rich areas in Asia.”[28]

In Mon territory the most serious infractions have occurred in Mon State’s Kyaikmayaw Township, with land unjustly acquired from residents by various domestic companies planning to establish extensive cement production in the region (this case is discussed in full in Section F).

With plans recently announced in Moulmein, the capital of Mon State, of a USD 386 million cement plant by Thailand-based Siam Cement Group and designs for an electric power plant run by another Thai-based company, potential risks to farmers’ land security in the region continue to arise.[29] Ko Than Hlaing, a senior construction engineer originally from Moulmein, emphasised the importance of community members being able to share in the benefits of investment rather than solely bearing the costs.

“We always welcome rural developments in our country. It is a great opportunity to create jobs in our areas… The unemployment rate for young people in rural areas is increasing in our country. They should be offered job opportunities [as a result of] Foreign Direct Investment [FDI]. Domestic citizens should get capacity development from FDI.”[30]

Compounding the threat to farmers’ land rights is the spate of State-backed development projects brought on by new investment designed to improve the country’s infrastructure as it seeks legitimacy in global markets. In June 2013 HURFOM reported on destruction of land along the route of a road construction project planned to link Mon State’s Thanbyuzayat Township to Thailand via the border town of Three Pagodas Pass. With 280 acres of land destroyed since the project commenced in 2011, sources allege that on 7 June 2013 Col. Aung Lwin, Border Security Affairs Minister, commanded the chief engineer of the Public Construction Department to focus singlehandedly on the road’s construction, even where this was at the expense of residents’ land.[31]

3. The current legal framework of land rights in Burma

In 2012 various land laws were repealed[32] and a number of new laws were passed concerning farmers’ rights to land and the acquisition of land by other agents. Below is an overview of some of the key laws in effect at the time of writing.[33] The contention is that these new laws have been used to (1) vindicate past land confiscations, thus avoiding land restitution and compensation payments, (2) deny the rights of farmers in on-going land conflicts, and (3) facilitate future unfair acquisitions of farmers’ land.

(i) Constitution of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar (2008)

The 2008 Constitution declares Burma to be a market economy in which private property rights are recognised (Articles 35 and 37) and requires the government to enact necessary laws to protect peasants’ rights (Article 23). However, the 2008 Constitution maintains the State as the ultimate owner of all land (Article 37) and thereby preserves the government’s right to forcibly acquire land from its citizens.

(ii) Foreign Investment Law (2012)

The 2012 Foreign Investment Law passed in November of that year stipulates that foreign agents can invest up to 100% in any one project (Article 9). The law regulates investment in various ways, stating that:

- Agricultural projects must be carried out as a joint venture with a citizen (Article 35).

- Foreign investors can lease land for up to 50 years, which can be extended up to a total of 70 years (Article 31).

- Investment is restricted where the project can “affect the traditional culture and customs of the national races within the Union” or is an agricultural project that could be

- carried out by citizens (Article 4).

However, the Myanmar Investment Commission (MIC), a body appointed by the government to oversee foreign investment (Article 11), is given considerable authority to overrule these regulations. Notably, it may allow restricted investments for “the interest of the Union” (Article 5) and stipulate longer land leases in less developed, difficult to access areas (Article 36).

(iii) Farmland Act (2012)

The Farmland Act was passed on 30 March 2012 and came into force on 31 August 2012 with a set of accompanying regulations. The law upholds the State as the owner of all land but permits the “right for farming” to individuals in order that the country’s agricultural production may develop (Article 3). Disposing with socialist-era legislation, the act formalises the 2008 Constitution’s commitment to a market economy, putting in place a system of private land ownership where citizens and other bodies may legally own, sell and otherwise transfer land.

By this law, the right to use farmland is recognised when land is formally registered in the owner’s name, notably excluding rights to land conferred by informal customary ownership practices (Article 4).[34] Land use rights are to be managed by Farmland Management Bodies (FMBs) at Village/Ward, Township, State and Central levels, and registered by the Settlement and Land Records Department (SLRD). Individuals with claims to land must apply to their Township’s SLRD for a Land Use Certificate (LUC) and pay a fee to register their land should the SLRD decide in their favour (Articles 5-8).

Far from establishing fully secure land tenure, various conditions are made on the right to use land (Article 12) with failure to comply punishable by anything from a fine to the revocation of the owner’s LUC. Notably, conditions include:

- The use of land only for the purpose specified in its LUC, unless permission is granted from the relevant FMB. Farmers are prohibited from growing anything other than their regular crop or using their land for non-agricultural purposes.

- An obligation to cultivate land at all times, refraining from leaving it fallow without sound reason.

Further jeopardising farmers’ land security, State ministries reserve the right to utilize farmland for projects in the long-term interest of the State (Article 29), although compensation must be paid (Article 26) and land returned if the project is terminated or not carried out within the prescribed timeframe (Article 32). Whilst compulsory sale of land is a rights-respecting feature of law in many countries there are serious concerns in Burma’s case, given a precedent of State abuse of the legally enshrined right to appropriate land.[35] This is compounded by the fact that the law lacks clear guidance on when and for what reasons the State may demand sale of land, and on how compensation is to be decided.

The Farmland Act does permit “agriculturalists associations” (Article 38). However, there is no mechanism to refer land appeals to an independent judicial body (Articles 22-25). Instead, village/ward FMBs are designated as responsible for deciding land disputes, with appeals to be lodged first with the Township FMB, then the District and finally the State FMB that holds ultimate decision-making power.

(iv) Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Lands Management Law (2012)

The Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Lands Management Law (hereafter the “VFV Law”) was also passed inMarch 2012. In effect the law expands on the 1991 Wasteland Instructions, granting rights to investors looking to acquire vacant, fallow or virgin land. By this law:

- Land may be acquired by citizens, joint-venture investors (by approval of the MIC) or government bodies for the purposes of agriculture, mining or other government allowable purposes (Articles 4-5).

- Up to 5,000 acres of land may be granted at any one time, up to a maximum of 50,000 acres (Article 10).

- Lease periods of up to 30 years are allowed (Article 11).

Decisions to grant land are made by the Central Committee for the Management of Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Land chaired by the Minister for Agriculture and following recommendations from various government bodies (Articles 6-7). Powers conferred on the Central Committee include the right to grant more than 5,000 acres of land for projects in line with State interests (Article 10).

In conjunction with the Farmland Act the VFV Law designates the right for investors to acquire any land not formally registered with a LUC, superseding claims to land conferred by customary ownership practices. Whilst the law acknowledges that farmers may in fact be cultivating formally unregistered areas of land (Article 25), where they lack official documentation their rights are left unrecognised. If LUCs are not held then compensation need not be paid to cultivators, nor must their consent to acquisition be obtained.

Farmers are offered limited legal recourse to protest such acquisitions. Again no independent judicial body is assigned to handle disputes, with the Central Committee given responsibility for handling contested cases (Article 25). Offering some protection, the accompanying VFV Rules stipulate that the Central Committee must ensure that farmers cultivating unregistered land are not unjustly dealt with (Rule 52). However, the VFV law makes clear that protest is subject to severe legal consequences: individuals protesting against land acquisition by interfering with the concerned project’s progress are liable to penalties of up to 3 years imprisonment or a 1 million kyat fine (Articles 26-28).

Farmers are offered limited legal recourse to protest such acquisitions. Again no independent judicial body is assigned to handle disputes, with the Central Committee given responsibility for handling contested cases (Article 25). Offering some protection, the accompanying VFV Rules stipulate that the Central Committee must ensure that farmers cultivating unregistered land are not unjustly dealt with (Rule 52). However, the VFV law makes clear that protest is subject to severe legal consequences: individuals protesting against land acquisition by interfering with the concerned project’s progress are liable to penalties of up to 3 years imprisonment or a 1 million kyat fine (Articles 26-28).

It is worth noting that concerns over land security under the VFV Law are applicable to land owned by the vast majority of Burma’s farming population. In June 2013 it was claimed that 85% of farmers in the country lacked currently valid paperwork for their land.[36] Reports have indicated few government efforts to facilitate swift land registration and there is a pressing need for the registration process to be streamlined and accessible to farmers looking to obtain LUCs.[37]

D. Pursuing land rights: 2011-13

Commenting on the current situation for Burma’s farmers, the Asian Legal Resource Centre stated in an ND-Burma report that:

“Almost daily, news media carry reports of people being forced out of their houses or losing agricultural land to state-backed projects, sometimes being offered paltry compensation, sometimes nothing.”[38]

Although HURFOM’s research shows that this observation is all too true, another trend has encouragingly emerged alongside it. With almost equal frequency, news outfits have been reporting on farmers taking action against unjust land acquisition.[39] Encouraged by President Thein Sein’s nominally civilian government and making use of new freedoms[40] granted by its reforms, farmers across Burma have been taking a stand against unjust land acquisition by demanding restitution for past confiscations, calling for fair treatment in on-going land disputes, and moving to secure rights over their land in the future.[41]

1. Mon farmers’ fight for their rights to land

Research confirmed Mon farmers’ participation in this surge of civil action. Information obtained from Ye and Kyaikmayaw townships from April to September 2013 is summarised below, alongside research from this period and HURFOM archive materials regarding Thanbyuzayat, Paung and Yebyu townships and other areas of Tenasserim Region. Case studies in Sections E and F expound in full on residents’ activities in Ye and Kyaikmayaw townships.

(i) Demands

Most farmers taking action against unjust land acquisition stated that the return of their land was their first priority,[42] largely due to the land’s current value. One farmer from Mae Gro village in Kyaikmayaw Township said:

Most farmers taking action against unjust land acquisition stated that the return of their land was their first priority,[42] largely due to the land’s current value. One farmer from Mae Gro village in Kyaikmayaw Township said:

“We want to get our land back since land prices are high now.”[43]

Several farmers seeking restitution deemed fair compensation at the land’s current market value to be an acceptable alternative where land is currently in use by its new owners and return is impractical.[44] Other farmers lodged more modest requests. One farmer from Kyaung Ywa in Ye Township said residents from his village had given up altogether on hopes of restitution for land confiscated from them in 2001 by Light Infantry Battalion (LIB) No. 591. Instead, they were appealing to be compensated only for the plants growing on their land at the time of its seizure.[45]

(ii) Letters of appeal

The most common activity reported by Mon farmers when tackling cases of unjust land acquisition was penning letters of appeal. Written appeals were recorded in Mon State’s Ye, Kyaikmayaw and Thanbyuzayat townships, in addition to Yebyu Township and other areas of Tenasserim Region.[46] These were variously directed to the President, government departments, senior military authorities, local administration, parliamentary representatives and the recently established Land Inquiry Commission (see below). Letters illuminated the range of abuses and perpetrators, from past to on-going land acquisitions and involving the military, local administration, investors and ethnic armed groups.

The most common activity reported by Mon farmers when tackling cases of unjust land acquisition was penning letters of appeal. Written appeals were recorded in Mon State’s Ye, Kyaikmayaw and Thanbyuzayat townships, in addition to Yebyu Township and other areas of Tenasserim Region.[46] These were variously directed to the President, government departments, senior military authorities, local administration, parliamentary representatives and the recently established Land Inquiry Commission (see below). Letters illuminated the range of abuses and perpetrators, from past to on-going land acquisitions and involving the military, local administration, investors and ethnic armed groups.

(iii) Defying authority

Several farmers were recorded as having defied the authority of unjust land acquisitions. Nai Tun Toung, 54, from Mae Gro village of Kyaikmayaw Township told a story that echoed narratives shared by a number of farmers who said they cultivated crops or built structures on land that had been unjustly taken from them but then never subsequently used.

“Since last year we have grown rice paddy on our land without permission from [June Industry Co. Ltd], even though we may face some problems from them. We don’t want to be silent…Whether they [the government] accept our letter [of appeal] or not we will grow paddy on our land for our daily food.”[47]

Correspondingly, a farmer from Kaloh village, Ye Township explained how in February 2012 he built a fence around land that was confiscated from him in 1992 for railway line construction but was never used for that purpose.[48] In a similar act of defiance, residents of Ye Township’s Tu Myoung village refused in June 2012 to pay an annual tax levied by the military in exchange for permission to work on land confiscated by LIB No. 586 in 2001.[49]

(iv) Refusal to accept unfair compensation offers

Various farmers who experienced investors’ attempts at unjust land acquisition told HURFOM that they, or others in their village, declined unsatisfactory offers of compensation even when company officials used threats to coerce the owners into signing compensation agreements.[50] Nai Tun Kyi, a 55-year old farmer from Mae Gro village in Kyaikmayaw Township, detailed his refusal to cooperate with the June Industry Co. Ltd. in 2011.

Various farmers who experienced investors’ attempts at unjust land acquisition told HURFOM that they, or others in their village, declined unsatisfactory offers of compensation even when company officials used threats to coerce the owners into signing compensation agreements.[50] Nai Tun Kyi, a 55-year old farmer from Mae Gro village in Kyaikmayaw Township, detailed his refusal to cooperate with the June Industry Co. Ltd. in 2011.

“They announced that they would give 100,000 kyat per acre, and, as it was a State project, they threatened that if we did not agree then they would take the land without compensation. The farmers, including my family, decided not to accept their small amount of compensation and refused to sign for it.”[51]

Ma Thin, 36, from Kyaikmayaw’s Ka Don Si village described repeated refusals to hand over her land to the Pacific Link Company.

“Other people have already sold their plantations to the [Pacific Link] company but we have no plan to sell ours yet, although the company has called on us five times already to sell to them. We will increase the price [asked] for our plantations, and the company can take it or not.”[52]

(v) Organised Protest

In one case, Mon farmers were documented to have participated in an organised protest against land confiscation. In May 2013 over 100 farmers from 14 villages in Paung Township gathered to protest against injustice in their communities, with land seized by the NMSP cited as a primary complaint (case detailed in Section C). The demonstration was recorded as the first of its kind in the township’s history. According to Nai Aung San, a protester leading the event:

“The purpose of the protest is to demand the same rights for all local people. If our demands do not succeed, we will know that the authorities are not properly committed to democracy.”[53]

(vi) Formation of farmers unions

Some Mon farmers took action by moving to establish union-based advocacy groups in an attempt to unite farmers and improve their standing in land-based conflicts. In 2012 a victim of the navy land confiscations on Kywe Thone Nyi Ma Island of Yebyu Township said:

Some Mon farmers took action by moving to establish union-based advocacy groups in an attempt to unite farmers and improve their standing in land-based conflicts. In 2012 a victim of the navy land confiscations on Kywe Thone Nyi Ma Island of Yebyu Township said:

Whilst the Myanmar Farmers Association (MFA) exists on a national level, the group has been criticised for representing the interests of high to middle income agribusiness players as opposed to championing the rights of the country’s smallholder farmer majority.[55] To work towards achieving a truly representative alliance, Mon farmers have exercised permissions granted in the 2012 Farmland Act and begun the process of registering their own Farmers Union.[56] Attempts to establish such a union failed in 2007, but enough political space may have opened up for dormant plans to now take root.[57]“If we create a union to support farmers’ rights, this will not happen again.”[54]

Nai Kao Tala Rot spoke to HURFOM about the formation of the Rehmonnya Agriculture and Farmers Union (RAFU) designed to represent Mon people living in Mon State, Karen State and Tenasserim Region. An ex-NMSP member, Nai Kao Tala Rot founded the Rehmonnya Labour Union (RLU) in 2009 and more recently accepted an offer from RAFU’s founder Nai Ron Dein to impart his experience to the establishment of the RAFU. The Union is in the process of official registration, with an application currently under consideration by township-level authorities.

“We give help to any people who request it from us…All people have the right to work on and cultivate [land], so we will be working on helping people whose land has been confiscated to claim their rights…We will continue to help [local people] fight for their rights if land confiscation happens again in the future…We hope our union can help them [local farmers] escape from a deep hole and the human rights abuses that happened in the past.”[58]

In addition to responding to cases of land conflict, Nai Kao Tala Rot detailed that the RAFU offers training for farmers covering land rights and land registration processes amongst other topics. Trainings have been given in Kyaikmayaw, Moulmein and Chaung Zone townships, with plans to begin activities Ye and Yebyu townships.

2. The Land Investigation Commission

Some appeals lodged by Mon farmers were directed to and investigated by the newly formed Land Investigation Commission, established in June 2012 in response to disquiet amongst the nation’s famers. Passed with 395 votes in its favour, the commission had the backing of broad parliamentary support.[59] The Land Investigation Commission is divided into nine groups composed of parliamentary representatives and tasked with investigating disputed land acquisitions since 1988 in specific regions. Notably, its mandate is limited to investigating cases and formulating recommendations and does not include or bestow decision-making capabilities.

Mon farmers’ complaints fall under the jurisdiction of Group 9, or the “Land Grab Inquiry Commission”, responsible for investigating disputes in Tenasserim Region and Karen and Mon states. The five-person group is led by U Htay Lwin, a member of the Upper House of Parliament, along with four Lower House MPs representing the different constituencies covered under the Commission’s authority.[60] The group began field research activities in late September 2012 with tours of various areas in Karen State.[61]

“As part of the Commission’s activities we have to survey land, make conclusions, consult any other facts or issues [relevant to the cases] and give feedback. We only handle cases after 1988,” said Mi Myint Than, a member of the Commission and Ye Constituency MP for the All Mon Regions Democracy Party (AMDP). “Six types of land confiscation cases have been submitted to parliament: Farms and plantations confiscated for the extension of military bases, to construct railway lines and motorways, build bridges and airports, establish companies, build [State-owned] factories and complete civil [agriculture and animal husbandry] projects…After exploring and observing the cases, we submit findings from our field trip to upper levels [of authority]. After coming back from field research, we have to meet and consult [with the upper levels] to share our and other groups’ findings. When we finish sharing our observations and conclusions we have to draft a plan of action [for the cases].”[62]

“As part of the Commission’s activities we have to survey land, make conclusions, consult any other facts or issues [relevant to the cases] and give feedback. We only handle cases after 1988,” said Mi Myint Than, a member of the Commission and Ye Constituency MP for the All Mon Regions Democracy Party (AMDP). “Six types of land confiscation cases have been submitted to parliament: Farms and plantations confiscated for the extension of military bases, to construct railway lines and motorways, build bridges and airports, establish companies, build [State-owned] factories and complete civil [agriculture and animal husbandry] projects…After exploring and observing the cases, we submit findings from our field trip to upper levels [of authority]. After coming back from field research, we have to meet and consult [with the upper levels] to share our and other groups’ findings. When we finish sharing our observations and conclusions we have to draft a plan of action [for the cases].”[62]

Given that investigations in Mon State commenced only in June of this year, results have yet to be seen.[63] For Mon areas, the nascent activities of the Land Grab Inquiry Commission Group 9 signal a step in the right direction, and HURFOM acknowledges the enormous task at hand and the significance of burgeoning efforts to collect and respond to farmers’ appeals. It is hoped that this report will serve as a research and advocacy tool to assist with these land survey endeavours and provide recent, supplementary data from Ye and Kyaikmayaw townships. Most cases presented herein occurred after 2005 and up until today and therefore suitably match the Commission’s mandate to cover land disputes originating after 1988. However, there are some clear reasons, outlined below, to doubt that the Land Investigation Commission represents a convincing attempt on the government’s part to improve processes and inadequacies currently inherent in land dispute resolution.

(i) Obstacles to investigations

Members of the Land Grab Inquiry Commission detailed various obstacles faced during the course of their inquiries. For example, MP Mi Myint Than described the failures to cooperate with investigations exhibited by senior military authorities.[64]

“When we requested that the [Southeast Command] Chief of the military meet and consult with us, he dispatched a junior to us who had only been in the military for two days. He [the replacement] was new to military service, so how could he tell us about the military? In my opinion, I thought that [the military authorities] did not want us to inspect them and uncover the truth.”[65]

Commission Member Daw Nan Say Awa, who also serves as the MP for the Phalon-Sawaw Democratic Party for Hpa-an Constituency, Karen State, reported that members of the Settlement and Land Records Department (SLRD) had failed to respond to requests from the group for assistance to investigations.[66]

Another obstacle was apparent during field surveys in Hpa-an Township, Karen State where the group’s investigations were hindered by farmers’ fear of reprisals from authorities involved in land confiscation. Mi Myint Than commended the efforts of other villagers, unaffected themselves by land disputes, who disregarded threats from village administrators and bravely assisted the Commission by encouraging hesitant farmers to discuss their cases.[67] Still, apprehension surrounding frank discussions of land disputes represents a substantial challenge to the Commission’s investigations as it pursues comprehensive and accurate data collection.

(ii) Lack of influence

Land Grab Inquiry Commission members interviewed by HURFOM displayed a genuine commitment to helping farmers pursue their rights to land. Speaking to HURFOM, Mi Myint Than emphasised the Commission’s freedom from government control and the impartiality of its members.

“We were chosen, not because of our relation to any cases, but because we were interested in solving the problems of the local people who have been affected [by land confiscation].”[68]

However, the potential of the Commission to influence outcomes is limited and the group’s mandate is purely investigatory in nature.

“When we give feedback [to farmers who lodged appeals] we will not be able to provide specific answers…We have to urge seniors [in positions of authority] to make sure that the owners get their land back,” continued Mi Myint Than. “We tried to reach out and increase public awareness about the issue as much as we could. We communicated to people close with us that they should pass our offers on to local people who want to get our help. We would like to help them escape from deep problems as far as we can, but it depends on the senior people [in government]…Although Myanmar has been changing into a democracy for two years, law and order is still weak. The people who have the right and power [to resolve land problems] are the [same] people who were involved in these kinds of issues in the past.”[69]

This sentiment was supported by events following the Land Investigation Commission’s first report to parliament in March 2013 concerning military land seizures.[70] The response was directed to the Land Investigation Commission as a whole, but has important implications for activities in Mon areas.

It was reported that between July 2012 and January 2013 the Land Investigation Commission received 565 separate complaints regarding military confiscations covering almost 250,000 acres of land.[71] However, on 16 July 2013 Burma’s Minister of Defence announced to parliament that only 18,364 acres of land reported on by the Commission would be returned to owners. He asserted that the remainder could not be returned as it was in use by military battalions or was too close to active military space to be safely used by civilians.[72] He also claimed that a number of complaints listed by the Commission had been perpetrated by other actors and unfairly blamed on the army.[73]

In Section C, HURFOM noted concerns that local and national-level corruption will continue to impinge upon justice and dispute resolution until laws provide for land acquisition cases to be investigated and decided by independent decision-making bodies. The government communication above evidences that without direct dispute resolution authority, the Land Investigation Commission’s efforts may remain toothless.

The Land Investigation Commission is also unable to expedite restitution of land or payment of compensation following the announcement of decided outcomes. Those farmers mentioned above and representing the small fraction of land designated for return by the military have yet to regain their farms and plantations. Despite hopes that land would be restored to former owners before the end of fertile monsoon season, no immediate actions were taken. Burma’s Union Parliament Speaker Thura Shwe Mann and Land Investigation Commission Member MP Pe Than were among the critics of the slow-moving land restitution process.[74] Whilst the Minister of Defence had initially promised that land would be returned in July of this year, on 23 August Presidential Office Minister U Soe Thein announced that land would be returned to farmers in October and contingent upon their ability to produce LUCs.[75]

3. Elusive progress

On the whole research showed that farmers’ vocal pursuit of their land rights has been met with little real progress. As detailed above, few cases of land disputes in Mon regions have been brought to satisfactory and just conclusions and most are accompanied by concerns about the methods of handling complaints. On a nationwide scale, the Land Investigation Commission’s limited impact showcases its restricted capacity to influence decisions that, instead, frequently remain in the hands of local, military, or state authorities that were themselves complicit in the disputes.

President Thein Sein promised[76] to develop “clear, fair and open land policies”, but his commitment to reform continues to be questioned. For example, the newly drafted Farmers’ Interests Promotion Bill remains silent on the issue of unjust land acquisition.[77] Current legislation still leaves the door open for investors to obtain vast areas of land from farmers whose rights are legally undefended. Worryingly, reports have also emerged of the country’s law being applied to arrest activists staging protests over land disputes.[78]

“Today the government is a government that neither takes action for you nor listens to your complaints,” said a legal agent from Thanbyuzayat Township. “The government does nothing and becomes a toothless government with no responsibility or accountability.”[79]

The question arises: what exactly is standing in the way of progress? The following sections explore some of these barriers using land dispute case studies from two different townships to analyse the obstacles Mon farmers’ face in their pursuit of just land rights. HURFOM stands alongside these courageous Mon farmers and calls for reforms to facilitate immediate and equitable recognition of their rights to land.

E. CASE STUDY 1: Past military confiscations in Ye Township

1. Case summary

As outlined earlier in the report, under military rule various factors conspired to bring about large-scale military confiscations of land in Ye Township, located in the south of Mon State. These confiscations largely took place after 1995 following the ceasefire between NMSP and Burmese military forces. As a zone newly accessible to the Burmese military and on the route of the Kanbauk to Myaing Kalay gas pipeline, Ye Township saw a surge of military battalions deployed to the area and subsequently seeking land.

As outlined earlier in the report, under military rule various factors conspired to bring about large-scale military confiscations of land in Ye Township, located in the south of Mon State. These confiscations largely took place after 1995 following the ceasefire between NMSP and Burmese military forces. As a zone newly accessible to the Burmese military and on the route of the Kanbauk to Myaing Kalay gas pipeline, Ye Township saw a surge of military battalions deployed to the area and subsequently seeking land.Victims of previous Ye military confiscations were revisited by HURFOM in 2013 and each reported losing between 2 and 40 acres of land with little or no compensation provided (see Appendix 2). Sums of compensation recorded were as low as 563 kyat for almost seven acres of land.[85] Often the fact that land was unregistered and officially classed as ‘vacant’ was used to justify failure to compensate land or the crops growing on it.[86]

Residents were frequently coerced into signing compensation agreements that were used to give an impression of legitimacy to military land acquisition. Nai Khin Mung Nyit from Koe Mile village had his 10-acre plantation confiscated by LIB No. 299 in 2001 on behalf of the Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry. He told HURFOM:

Residents were frequently coerced into signing compensation agreements that were used to give an impression of legitimacy to military land acquisition. Nai Khin Mung Nyit from Koe Mile village had his 10-acre plantation confiscated by LIB No. 299 in 2001 on behalf of the Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry. He told HURFOM:

“When they confiscated [the land], [the military] said they would compensate us. They took us to visit their base office in order to force us to sign [an agreement for the compensation]. They called us to visit five or six times. They gave 100,000 kyat to my oldest brother and then we five siblings divided this to take 20,000 kyat each. 100,000 kyat was not a lot of money, it could be spent on a child’s snack. But we were too afraid of them to refuse to sign our signatures.” [87]

To put that sum into perspective, at the time 100,000 kyat was roughly equivalent to a third or half of the profits generated from one durian harvest on a plantation of that size.[88] Although larger sums of compensation were offered to certain other residents in the area, the extent of the undervaluation of land that is central to providing families with income year after year is apparent. Today Nai Khin Mung Nyit’s plantation is valued at 10 million kyat.

2. The aftermath of military confiscations for Ye residents

From July to August 2013 HURFOM field reporters revisited victims of previously reported cases of military land confiscation in 14 villages in Ye Township and some in Lamine and Ye towns.[89] In five of those villages a large number of previously reported cases were no longer being disputed[90], whilst in another five various difficulties meant that little reliable data could be obtained.[91] Hence 105 on-going land dispute cases were confirmed in the surveyed areas and followed-up by HURFOM researchers (see Appendix 2).

In general, the confiscations under discussion took place in 2001 and research revealed the spectrum of farmers’ experiences in Ye Township over the 12 years following the loss of their land.

(i) Rental and re-purchase of land

After their land was confiscated, the majority of farmers continued to work on their properties for at least some period of time due to tenancy agreements with the land’s new military owners. In all villages surveyed, offers of tenancy agreements had been made to residents.[92] However, a letter of appeal noted that offers had not been made to farmers whose land had been classified as fallow.[93] Interviewees in Ayu Taung village suspected that the military had made different offers to different parties in order to create disunity amongst villagers and prevent them from uniting in collective protest.[94]

In many cases farmers were given permission to work on land for three to five years without incurring fees, particularly where they had received no compensation at the time of seizure.[95] However, in Koe Mile village farmers noted that the rent-free period officially granted to them was five years but, for two of these years, they were prevented from using their land.[96]

After rent-free periods ended, or where they were never granted, farmers were required to pay the military ever-increasing usage fees in exchange for permission to cultivate the land they had previously owned. According to Nai Kyaw Thein, 50, whose eight-acre plot of land was confiscated by LIB No. 586 in 2001:

“After the five years [rent-free period] we had to pay 550 kyat per rubber tree [growing on the plantation], 700 kyat per tree the following year, 800 kyat the next, and eventually 1,300 kyat”.[97]

“After the five years [rent-free period] we had to pay 550 kyat per rubber tree [growing on the plantation], 700 kyat per tree the following year, 800 kyat the next, and eventually 1,300 kyat”.[97]

Most interviewees reported that payments were decided on a per plant basis, with prices demanded varying from battalion to battalion. Fees being paid today hovered around 1,300 kyat per plant.[98] With plantation sizes ranging widely, villagers reported paying up to 1.5 million kyat per year in usage fees.[99] One villager told HURFOM that, with the price of rubber fluctuating and rent prices rising, he had at times been driven into debt by the payments levied on his former land.[100] It was also reported that the military occasionally demanded additional taxes from renting farmers[101] to cover arbitrary purchases or expenditures for the battalions. In one case concerning LIB No. 586, residents were told the collected taxes would be used to “fix the generator, host guests, and give presents to senior [members].”[102]

With few other options to earn an income, many villagers agreed to the rental arrangements. Some continue to pay usage fees on their former plantations to this day.[103] However, numerous interviewees said that they had been unable to afford the payments demanded and so could not rent their land.[104] Where this was the case in Kyonepaw and Kyaung Ywa villages, it was reported that businessmen from other areas had subsequently taken up rental contracts on villagers’ farms.[105]

Other residents said they refused rental agreements out of unwillingness to negotiate with the parties behind the confiscations. Nai Hlaing, 70, from Kyonepaw village described his resistance:

“They [the military] stopped approaching me after I refused to meet with them, and many times [to avoid meeting with them] I went to work instead, even though I was called [to meet with them] and sent a letter [being summoned to a meeting]. Although I did not go to meet them…I heard that they [were saying that they] would give five years permission to work [on confisc

ated land]…I did not go to my plantation after they confiscated it and did not ask for permission to work…My land was not affected when they built their battalion. They should not have confiscated it.”[106]

When farmers did agre

e to rent their land from the military, a variety of related abuses were recorded over the rental period. One farmer said:

“They [LIB No. 587] intimidated us, reminding us that the plantation belonged to them and we could not harm or destroy the plants while working on it even though we paid [them] the money. They said that it was not our property but theirs.”[107]

Another farmer described misco

nduct by LIB No. 343, saying:

“Although I was 70 at the time they abused us, taking our electricity and making us live in the dark.”[108]

In a third case, corruption amongst military authorities led to a villager having to pay rental fees again and again to multiple agents.[109]

Compounding their difficulties, renting farmers also reported facing insecure access to land, with rental agreements subject to being terminated at any time. Farmers from Kundu, Kyaung Ywa and Kan Hla villages detailed contracts being terminated after two to three years.[110] In both Kyaung Ywa and Kan Hla it was reported that threats had been used to intimidate farmers into giving up the land. In September 2013 HURFOM reported on a new group of farmers whose rental contracts on confiscated land were being terminated, with plantations being given to soldiers’ families. One of these farmers explained how this outcome was a result of his request for a reduction in rent:

“We met with an army major to discuss the price for 2013, but he refused our request to decrease the payment from 1,200 kyat to 1,000 kyat, which reflects the change in the price of rubber. On August 29 we went again to the major for negotiations but he said he would not sell the land to anyone and was instead planning to give the land to the families of soldiers. He was worried about military leadership hearing about the land disputes and conducting an investigation. We feared his words because he told us that he didn’t care about our situation and would ‘shoot back’ if needed.”[111]

Aside from renting out land, army battalions have also sought to make money from victims of confiscation in other ways. It was reported that army battalions in Kyonepaw, Kundu and Kyaung Ywa villages had recently offered residents the opportunity to buy back their land.[112] Many farmers’ commitment to regaining their land was such that they said they would accept, agreeing to give up to the full price they originally paid for it despite concerns about the land’s current poor condition.[113] However, Nai Aung Soe Myit, 40, from Kyaung Ywa village said:

Aside from renting out land, army battalions have also sought to make money from victims of confiscation in other ways. It was reported that army battalions in Kyonepaw, Kundu and Kyaung Ywa villages had recently offered residents the opportunity to buy back their land.[112] Many farmers’ commitment to regaining their land was such that they said they would accept, agreeing to give up to the full price they originally paid for it despite concerns about the land’s current poor condition.[113] However, Nai Aung Soe Myit, 40, from Kyaung Ywa village said:

A recurring narrative about the decline of formerly fertile land appeared in other interviews as well, and in general conditions were reported to have deteriorated once farmers were no longer actively cultivating their land. In several cases land lay unused by battalions and was covered in weeds.[115] Nai Kyaw Thein, whose land once encompassed 1,200 rubber trees, said:“Although the military has proposed that we can get back our plantations for half the price I do not want to buy it back because I would just get back the land, without any [income generating] plants. There are only tall grasses on the plantation now that I would have to clear out [to be able to plant crops] if I took it back so it would be a lot of work again.”[114]

“I love my plantation so much that [after his rental contract was terminated] I went to look at its condition and I was sad to see that my plantation was almost destroyed. They kept the plants that they could [use to] have fruit to eat and, as for the plants that could not provide fruit, they cut them all down and did not replant them. So now there are long grasses [on the plantation] and it looks like a jungle.”[116]

In other cases, land had been rented out to companies whose lack of expertise in farming had caused the destruction of land and plants.[117] Overuse of chemicals by inexperienced cultivators was given as one cause of this decline.[118]

(ii) Loss of livelihoods and labour migration

For farmers in Ye Township who either refused to pay usage fees, had rental contracts terminated, or were never given the option to continue working their plantations for a cost, land seizures resulted in a damaging blow to their livelihoods. Some were fortunate enough to own multiple plantations to offset the loss of one, but for others their single plots of land represented their sole source of income.[119] In addition, with up to eight years of continuous investment and labour needed to see a profit from rubber trees, one of the primary crops in Ye Township, the loss of plants for little or no compensation created a further affront to the farmers’ years of effort.

For farmers in Ye Township who either refused to pay usage fees, had rental contracts terminated, or were never given the option to continue working their plantations for a cost, land seizures resulted in a damaging blow to their livelihoods. Some were fortunate enough to own multiple plantations to offset the loss of one, but for others their single plots of land represented their sole source of income.[119] In addition, with up to eight years of continuous investment and labour needed to see a profit from rubber trees, one of the primary crops in Ye Township, the loss of plants for little or no compensation created a further affront to the farmers’ years of effort.

“I want to provide a livelihood for my family,” said one interviewee. “So when my plantation was confiscated I was like a person with broken legs.”[120]

Farming families that lost their plantations were left to find new sources of work. One former landowner said:

“Now I work digging wells, cutting grass and working on other people’s plantations.”[121]

However, several farmers were reported to have migrated to other parts of the country or Thailand to seek work due to shortages of work opportunities in their native communities.[122]

Some interviews illustrated that children had shouldered their families’ financial burdens by working to support parents who lost farmland or plantations.[123] In some cases, this inverted dependency created friction for adults who had to shift from the role of breadwinner to relying on the income generated by younger members of the family. Mi Khin Win, a resident on Kan Hla village, told HURFOM:

“My father is still upset now about his plantation, and although we [Mi Khin Win and her siblings] give him a share [of our wages] he does not want to take it because he says that he has not done any work to get the money. To this day he says that if the plantation had not been confiscated by the military then his family would not be in a difficult situation.”[124]

Despite various testimonies collected about the loss of livelihoods, HURFOM research suggests that it is likely that the full extent of hardship faced by many families in Ye Township following confiscations remains undocumented. Field reporters described a recurring sense that some interviewees were too embarrassed to admit the full scope of financial difficulties that befell following their loss of land.[125]

(iii) Attachment to land and the toll of its loss

Many farmers expressed a deep attachment to their land and, as a result, a heavy emotional toll associated with its loss. Nai Hlaing, 70, from Kyonepaw village told HURFOM that despite refusing to rent his plantation from its new military owners, he helped them put out a fire on the land.

Many farmers expressed a deep attachment to their land and, as a result, a heavy emotional toll associated with its loss. Nai Hlaing, 70, from Kyonepaw village told HURFOM that despite refusing to rent his plantation from its new military owners, he helped them put out a fire on the land.

“Although the land does not belong to me anymore I still love it because I cultivated it for many years.”[126]

In 2012 a farmer in Chapon village told HURFOM that the connection he felt to his land had prevented him from migrating for work, despite the fact that the little land left to him after confiscation was not sufficient to support his family.

“After [some of] my land was confiscated, I wanted to go abroad like other people did but I could not leave my remaining four acres even though they didn’t provide enough income. There were many people like me who could not leave their land.”[127]

One young son of a land loss victim concluded:

“I had to send my father to the hospital three times because he was depressed [after troops confiscated the family plantation].”[128]

3. Widespread appeal, poor results

After years of hardship faced by farmers in Ye Township, the advent of President Thein Sein’s nominally civilian government and the end of decades of direct military rule ushered in a wave of public demands for rights over confiscated land. The initiation of democratic reform in 2011 was not the first catalyst for farmers in Ye Township to speak out against land seizures,[129] but complaints began to be heard at a hitherto unprecedented frequency.

Over the past few years, former residents of Chapon village began trickling back home in search of land restitution after being displaced by confiscations perpetrated by Navy Unit No. 43.[130] Farmers in Tumyoung village refused to pay annual rental fees to Light Infantry Battalion (LIB) No. 586, instead demanding the return of their land.[131] Formal letters of appeal were sent by residents in villages throughout Ye Township to the government and members of parliament.[132] By various means, the victims of past land confiscations began to make their voices heard.

(i) Residents demand land restitution and fair compensation

On the whole, residents requested for the return of their land or, failing that, fair compensation as demonstrated in a letter of appeal submitted by a group of former landowners from Ye Township. The document illustrates people’s desire to move on from past hardship while emphasising the need for justice and land rights to be recognised by the current administration. The letter concludes, “In order to be a dutiful government, the government needs to repay residents for their loss.”[133]

“People should not point to and look back on mistakes from that period of time, although many pains and problems were caused in the conflict period. It is better, if there is the opportunity, to make a new start and heal the injuries experienced by residents in the conflict period…the military confiscated many pieces of land to extend their military bases, which included many cases of corruption. However, some of the problems [faced

“People should not point to and look back on mistakes from that period of time, although many pains and problems were caused in the conflict period. It is better, if there is the opportunity, to make a new start and heal the injuries experienced by residents in the conflict period…the military confiscated many pieces of land to extend their military bases, which included many cases of corruption. However, some of the problems [faced

by residents] can be solved. Therefore we, the residents, have written this letter of appeal to be submitted to the authorities and other departments.”[134]The letter was written on behalf of all victims of military confiscations in the region, many of whom it said were unaware of their legal rights regarding land taken from them. It demanded that: (1) authorities account for all military land confiscations in the region and justify them by law, (2) land involved in unjustifiable seizures be returned to residents, and (3) in the remainder of cases compensation be paid for crops growing on the land at time of seizure. The letter called for assistance to help farmers gain secure rights over currently held land and avoid future land conflict, recommended that Ye farmers’ rights under new land laws be explained to them, asked that help be given to residents to formally register their land, and demanded that rights to registered land be fully respected by the authorities in the face of prospective investment acquisitions.

(ii) Disappointing outcomes

Thus far, such appeals have produced disappointing results, and HURFOM’s research revealed few instances in which confiscated land had been designated for return. There were some promising indications in Koe Mile village regarding land confiscated by the military on the behalf of the Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry. In 2012 the Ministry told farmers that their land would be returned to them, and asked locals for 8,000 kyat per acre for confiscated land to be measured prior to restitution, saying that LUCs would be given to mark the return of land. However, to date the papers still have not been issued. Whilst some Koe Mile farmers have begun to cultivate their land again regardless, some are continuing to appeal for LUCs, recognising that without them their land rights remain deeply insecure in the current legal setting.[135] One Koe Mile resident said:

“The forest department has already measured the land to be given back but the permission [to cultivate on it] has not yet been given. We are not sure whether we will get the permission or not, but we are still hoping.”[136]

(i) Confiscations by LIB No. 343 and 587: a failure to condemn and weak legal protections

A series of correspondence regarding confiscations by LIB Nos. 343 and 587 in Ayu Taung and Hnin Sone villages provides insight into key difficulties faced by Ye farmers seeking justice for abuses of the past.

In late April 2012 Mi Myint Than, the Ye Township constituency MP, submitted a letter of appeal on the behalf of farmers in Ayu Taung and Hnin Sone villages. Records showed that LIB No. 343 had acquired 360 acres of land in Ayu Taung and LIB No. 587 appropriated 224 acres in Hnin Sone. Mi Myint Than condemned such large-scale military land acquisitions, telling HURFOM;

“I think that they chose [to confiscate land in] areas suitable for business. If the government set a specific limit, 50 or 100 acres of land for each military base depending on whether it is big or small, the situation would be solved.”[137]