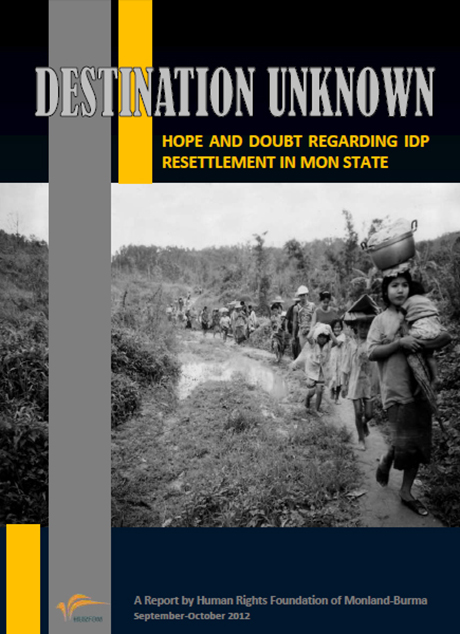

DESTINATION UNKNOWN: HOPE AND DOUBT REGARDING IDRESETTLEMENT IN MON STATE

I. Executive Summary

The growing optimism surrounding Burma’s political and social transitions has begun to be accompanied by ambitions to resettle displaced communities along the country’s border with Thailand. As the notion and its attendant proposals continue to proliferate, it seems timely to assess how the communities directly affected by this prospect feel about resettlement. Interviews were conducted with 61 Mon internally displaced people (IDPs) who expressed an array of views ranging from excitement for better jobs in new locations to utter refusal for fear of renewed conflict.

The growing optimism surrounding Burma’s political and social transitions has begun to be accompanied by ambitions to resettle displaced communities along the country’s border with Thailand. As the notion and its attendant proposals continue to proliferate, it seems timely to assess how the communities directly affected by this prospect feel about resettlement. Interviews were conducted with 61 Mon internally displaced people (IDPs) who expressed an array of views ranging from excitement for better jobs in new locations to utter refusal for fear of renewed conflict.

Concerns in the IDP community that relocation could lead to a recurrence of violence or exploitation may seem unfounded to those flushed with enthusiasm for Burma’s brisk pace of reform. However, it is precisely because of this rapid shift, after fifty years of a deeply entrenched system of repression, that many ethnic communities are unable to abruptly shed their enduring memories of systematic injustice. Similarly, for people in remote areas, there has not yet been adequate evidence of improvements to daily life or sufficient trust built between disparate groups to warrant immediate, broad-based support.

Importantly, almost all interviewees that addressed resettlement used “if” to describe their opinions, explaining that relocation is attractive only if adequate security, employment, education, and healthcare services are provided. This highlights fundamental priorities among IDPs, but also showcases the lack of information currently granted to internally displaced people. For those that had heard about relocation, many did not know if it was true, or where and when they might go, or if it even applied to them.

This incomplete information sharing has led to resettlement constituting little more than a rumor in IDP sites, and the consequent anxiety and confusion has been unnecessary and detrimental. The process needed to develop resettlement programs offers a singular opportunity to build trust with IDP communities by employing an inclusive and participatory approach.

The varying opinions and levels of support for resettlement demonstrated in this report serve as a key indicator that the IDP community is not a homogeneous group about which conclusions can be easily or independently reached. Some IDPs reported enjoying new freedoms and infrastructure projects, while other accounts were framed by doubt, exhibiting vivid memories of past abuses and few observations of significant change. In any case, each individual IDP or IDP family has a unique set of values and experiences that will define what an agreeable future looks like, and each must be given the chance to make free, prior, and informed decisions regarding engagement with resettlement programs.

This report’s primary aim is to amplify the voices of Mon IDPs and encourage the incorporation of their opinions into the development of resettlement agendas. We urge that the President Thein Sein government, the New Mon State Party, and associated international organizations be directly accountable to IDP populations by respecting their narratives and promoting full transparency in every stage of the process. While recent, positive changes may provide compelling reasons for people to return, they should not completely overwhelm considerations of why they left.

II. Methodology

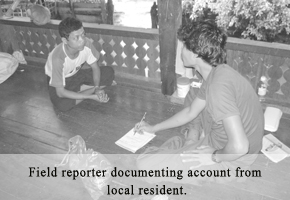

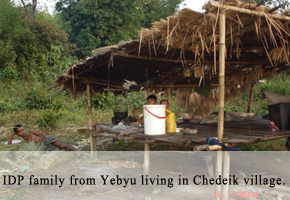

Since 1995, HURFOM has been cataloguing the voices of local civilians and documenting human rights violations committed by the previous military regime, the army and its supporters. For this report, four HURFOM field researchers conducted interviews with 61 Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) who live in the resettlement sites of Halockhani, Baleh Done Phai, Jo Haprao, Panan Pone, Suvanabhom, Chedeik, Burk Surk, Meip Zeip and Ban Don Yan refugee camp. Interviews were collected over four weeks in August and September 2012. The various resettlement sites visited by the researchers can be categorized into New Mon State Party (NMSP) administrative areas and sites located outside NMSP control and closer to Government Army camps. The 61 testimonies consist of 9 interviews from Halockhani, 4 interviews from Baleh Done Phai, 7 from Jo Haprao, 10 from Panan Pone, 2 from Suvanabhom, 10 from Chedeik, 5 from Meip Zeip, 10 from Ban Don Yan, and one interview from Mawgyi in Yebyu Township. The remaining three interviewees chose not to disclose their current locations. The interviews conducted in Ban Don Yan refugee camp were with individuals that formerly lived as IDPs before crossing the border into Thailand and reflect this previous period in time. 19 of the interviews were collected by telephone and follow-up interviews were conducted with some IDPs.

Attempts were made to contact t he relevant international aid groups currently serving Mon internally displaced populations, but interviews were declined due to the sensitive nature of current resettlement talks. Discussions with Mon service providers from local health, education, and aid organizations are presented herein.

he relevant international aid groups currently serving Mon internally displaced populations, but interviews were declined due to the sensitive nature of current resettlement talks. Discussions with Mon service providers from local health, education, and aid organizations are presented herein.

In addition to new materials and interview transcripts, this report uses information and photos drawn from HURFOM’s previous reports and extensive database developed over 17 years of documentation in southern Burma. Some facts in this report may have already been published in HURFOM’s print issues of the Mon Forum or online. Field researchers commented that some interviewees did not discuss resettlement, and this is noted in the report’s calculations regarding IDP resettlement opinions. In some cases, the names of sources have been changed or their nicknames were used for their protection, but whenever possible, HURFOM uses real names with permission from the individuals.

III. Background

The contemporary history of Burma, also known as Myanmar, is often compressed into a handful of prominent dates comprising coup d’états, civil and ethnic resistance, military crackdowns, ceasefires, elections, and a horrific natural disaster. While these are meaningful and momentous landmarks along the country’s trajectory, an equally powerful force shaping the lives of Burma’s people is found in the stretches of time between the great crises, in the long months and years that were slowly sculpted by varying degrees of uncertainty, distress, job and food insecurity, and conflict.

It is helpful to consider this broader view of the last half century in Burma in relation to its sizeable population of internally displaced people. Recent estimates by the UNHCR and T hai-Burma Border Consortium (TBBC) place the country’s internally displaced population between 350,000 and 450,000, many of whom have been living in resettlement sites for a decade or longer. Their experiences encompass much more than one-dimensional points in time, and the pace of current reforms may be difficult for some deep-seated assumptions to match. After a wave of violence or abuses crashed, it pulled back, leaving a trail of hardship that could saturate local communities for years to come.

hai-Burma Border Consortium (TBBC) place the country’s internally displaced population between 350,000 and 450,000, many of whom have been living in resettlement sites for a decade or longer. Their experiences encompass much more than one-dimensional points in time, and the pace of current reforms may be difficult for some deep-seated assumptions to match. After a wave of violence or abuses crashed, it pulled back, leaving a trail of hardship that could saturate local communities for years to come.

In southern Burma, the Karen, Mon and Tavoy IDP communities are often interconnected, and military offensives or large-scale development projects rarely affected one group alone. Conversely, resettlement sites on both sides of the Thai-Burma border were home to various ethnic groups that shared countless experiences. It is beyond the scope of this report to detail the myriad actors and influences affecting displacement over the past fifty years, and the single objective remains to elevate the voices of current Mon IDPs as changes continue to impact their lives and their country.

A. Protracted conflicts

Mon State in southern Burma is neatly wedged between the Andaman Sea, Karen State, and the western border of Thailand. The slender strip of coastal land is currently home to a significant number of internally displaced people (IDPs), primarily living along the state’s eastern border in areas controlled by the New Mon State Party (NMSP), the predominant ethnic Mon armed resistance group. TBBC recently published IDP population figures for Ye Township alone at 40,000[1], and the total for the state is thought to be almost double that. Karen State to the northeast and Tenasserim Region to the south together accommodate an additional 184,400 IDPs.[2]

Bouts with conflict-driven displacement are not new to Mon people, whose kingdom once spanned much of Thailand and Burma and frequently warred with competing ethnic groups. The 1700s brought increasing incursions by ethnic Burmans into Mon territories, eventually culminating in the defeat of the last Mon ruler in 1757. Less than seventy years later, Mon people in southern Burma were living under British colonial rule. Well before Burma gained its independence in 1948, political disagreements and internal conflicts ignited between the Burman majority and ethnic group leaders.

While the 1947 Panglong Agreement provided a framework for federalism in Burma, the eastern Mon and Karen ethnic groups were not included as semi-autonomous states, and for many the dream of federal union died with General Aung San. Much of post-World War II Burma was in tatters, with flare-ups between ethnic groups in the rural countryside and civil war gripping the central and southern regions. Mon and Karen leaders, determined to take up arms and fight the central government, faced growing resistance as the government command increased its defense budget and intensified offensives in ethnic areas. However, the Burmese Army was unable to suppress the rebellions, and the civil war grew.

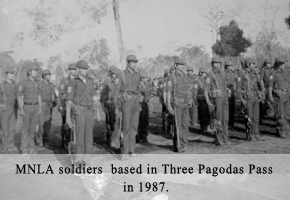

Significant flight from Mon communities began during the Mon People’s Front (MPF) insurgency between 1948 and 1958, when thousands of people left their villages to escape fighting with the parliamentary government. After the MPF surrendered in 1958, the New Mon State Party (NMSP) was formed, and its Mon National Liberation Army (MNLA) took up the banner of armed resistance against the Burmese Army and central government. The next few years saw less direct combat, but no improvements in ethnic rights and sustained tension among disparate groups. However, in March 1962, the military coup led by General Ne Win catalyzed the NMSP’s early secessionist objectives, and marked the beginning of socialist rule and a profoundly grim period for the country’s ethnic minorities. The military crept in to every aspect of society, tightening its grip on commerce, religion, education, politics, and national identity.

One of the more notorious strategies employed by the Ne Win government and his armed forces was the “four cuts campaign” that aimed to head off support for ethnic rebel groups thought to be flowing through Mon civilian communities. The “four cuts” refer to the targeted interruption of information, recruits, food supplies, and funds in rural villages in order to undermine insurgent forces. The initial years of the ruthless counter-insurgency approach resulted in hundreds of displaced rural ethnic villagers,[3] and variations of the tactic have continued until now.

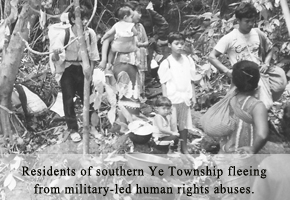

A 40 years old New Mon State Party schoolteacher, said that in the past 15 years, most residents from southern Ye and northern Yebyu Townships suffered some consequence from the four cuts campaign.

“I’ve been serving as a Mon National School teacher for IDP children since 1995. Based on what I’ve seen, Mon people arrive at the IDP camps due to direct effects from the SLORC and SPDC militarization policies and the four cuts campaign. For some of my students’ families from northern Yebyu, where Mon insurgencies were most active, the Burmese battalions arrived in their villages and burned everything to the ground because the residents were accused of being linked with armed rebel groups. When the NMSP and its armed force, the Mon National Liberation Army, launched military offensives against the Burmese Army before the 1995 ceasefire, many rural Mon villages were incinerated. People had to flee to these [IDP] areas without any of their possessions.”

After seizing political power from pro-democracy demonstrators in 1988, the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) hoped to decisively cripple the remaining ethnic armed forces. In February 1990, immediately following a Mon National Day celebration held by NMSP members, hundreds of Burmese Army troops launched attacks on the NMSP headquarters in the border area of Three Pagodas Pass. The MNLA was unable to fend off the strike, and the Burmese Army overwhelmed the headquarters and many MNLA bases. This devastating blow initiated an enormous exodus of Mon people to the country’s easternmost areas and across the border to Thailand.

B. The MNRC and Mon resettlement sites

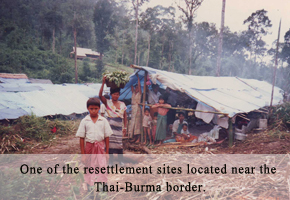

To attend to and assist the sudden wave of conflict-affected people along the border, the Mon National Relief Committee (MNRC) was created in February 1990 to provide food, shelter, and legal assistance. At the time, large relief agencies had not begun to operate in the border region and funding came primarily from local Thai-Mon community members and Buddhist monks living in Thailand. Starting that same year, Thai authorities permitted the establishment of nine refugee camps on Thai soil, which immediately received between 8,000 and 9,000 Mon displaced people. The refugee camps were designed with time limitations and severe restrictions on movem ent, but international aid organizations were later able to provide food assistance, education, and medical care to Mon resettlement sites on both sides of the border.The three main Mon IDP resettlement sites developed during this time were Halockhani, Bee Ree, and Tavoy, and many of their current residents have lived there since they were displaced 17 years ago. The first and largest of these, Halockhani, was founded in 1994 to shelter the thousands of Mon people fleeing from civil war, torture, forced porter duty, sexual harassment, and arbitrary extortion inside Burma. In addition, 2,000 newly displaced people arrived at Halockhani to escape widespread forced labor conscription taking place along the 110 miles of the Ye-Tavoy railway construction. In February and March of 1994, despite appeals from the MNRC and Mon refugee community, Thai authorities forcibly repatriated 6,000 Mon refugees living in the camps in Thailand to Halockhani camp in Burma. Four months later, Burmese troops attacked Halockhani, and throngs of Mon people rushed back into Thailand.According to Nai Brai, a former New Mon State Party township administration member, the Mon National Relief Committee received and resettled an estimated 400 households from northern and western Yebyu Township after the Burmese battalion No. 282 and 273 destroyed their homes between 1994 and 1995.Outside of the formal IDP camps, most of the IDP families living in the Meip Zeip, Krone Baing, Weng Nike, and Thee Chaung IDP village sites in NMSP-controlled areas of Tavo

ent, but international aid organizations were later able to provide food assistance, education, and medical care to Mon resettlement sites on both sides of the border.The three main Mon IDP resettlement sites developed during this time were Halockhani, Bee Ree, and Tavoy, and many of their current residents have lived there since they were displaced 17 years ago. The first and largest of these, Halockhani, was founded in 1994 to shelter the thousands of Mon people fleeing from civil war, torture, forced porter duty, sexual harassment, and arbitrary extortion inside Burma. In addition, 2,000 newly displaced people arrived at Halockhani to escape widespread forced labor conscription taking place along the 110 miles of the Ye-Tavoy railway construction. In February and March of 1994, despite appeals from the MNRC and Mon refugee community, Thai authorities forcibly repatriated 6,000 Mon refugees living in the camps in Thailand to Halockhani camp in Burma. Four months later, Burmese troops attacked Halockhani, and throngs of Mon people rushed back into Thailand.According to Nai Brai, a former New Mon State Party township administration member, the Mon National Relief Committee received and resettled an estimated 400 households from northern and western Yebyu Township after the Burmese battalion No. 282 and 273 destroyed their homes between 1994 and 1995.Outside of the formal IDP camps, most of the IDP families living in the Meip Zeip, Krone Baing, Weng Nike, and Thee Chaung IDP village sites in NMSP-controlled areas of Tavo y region were victims of armed conflicts between the New Mon State Party and the SLORC from 1992 to 1995. Mon soldiers seeking food and shelter would enter rural communities, potentially drawing the attention of Burmese Army troops that would reduce the villages to ash.

y region were victims of armed conflicts between the New Mon State Party and the SLORC from 1992 to 1995. Mon soldiers seeking food and shelter would enter rural communities, potentially drawing the attention of Burmese Army troops that would reduce the villages to ash.

C. politics and investments

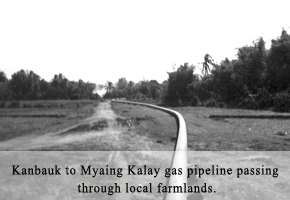

When the SLORC came to power in 1988, foreign corporate interests were granted permission to invest capital in Burma’s natural resource industries such as timber, gems, fishing, oil and natural gas. In turn, ASEAN adopted a policy of “constructive engagement” with the country. In May 1990, British company Premier Oil signed the first gas contract with Burma’s military government, and two years later, French oil company Total reached an agreement to harvest offshore gas in the Andaman Sea. In early 1993, the PTT Exploration and Production Public Company (PTTEP), one of Thailand’s biggest oil and gas enterprises, was determined to buy natural gas from Burma. On their behalf, in mid-1994 the Thai government signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Burma’s military government to access natural gas in Burma’s offshore Yadana gas field, a deal that reaped the Burmese government USD 400 million in one year from PTTEP. The Thai company also embarked on joint ventures with UNOCAL from the U.S. (now Chevron) and the Myanma Oil and Gas Enterprise (MOGE). Hundreds of villages across Mon State and Southern Burma were directly impacted by these large-scale development projects. After construction began on the Yadana gas pipeline in 1994, the SLORC established new military bases and stepped up their offensives against the MNLA in Yebyu Township of northern Tenasserim Region. Concurrently, Thai and border authorities increased their pressure on Mon leaders to engage in peace talks with the SLORC in an attempt to soothe investors and safeguard the lucrative gas project. Rebel activities threatened the investment climate as viewed by foreign companies, and the Thai government was resolute that a ceasefire between the military regime and rebel armed forces must be signed. NMSP leaders were still reeling from the Thai army’s forcible repatriation of Mon refugees, and they refused to engage with the peace process.

Hundreds of villages across Mon State and Southern Burma were directly impacted by these large-scale development projects. After construction began on the Yadana gas pipeline in 1994, the SLORC established new military bases and stepped up their offensives against the MNLA in Yebyu Township of northern Tenasserim Region. Concurrently, Thai and border authorities increased their pressure on Mon leaders to engage in peace talks with the SLORC in an attempt to soothe investors and safeguard the lucrative gas project. Rebel activities threatened the investment climate as viewed by foreign companies, and the Thai government was resolute that a ceasefire between the military regime and rebel armed forces must be signed. NMSP leaders were still reeling from the Thai army’s forcible repatriation of Mon refugees, and they refused to engage with the peace process.

D. ceasefire and Increased displacement

After a year of armed struggle and fierce pressure coming across the border from Thailand, on June 29, 1995, the NMSP and its armed wing signed a ceasefire with the SLORC regime, later to become the State Pace and Development Council (SPDC) in 1997. The ceasefire initiated a period of severe human rights abuses and the continuation of the military’s four cuts campaign strategies in rural villages. Before 1995, there were three Burmese Army battalions stationed around NMSP-controlled areas, and by 2000 there were more than 20.The years after the 1995 ceasefire saw a vast increase in displacement triggered by armed conflict and massive development projects. Thousands of ethnic Mon, Karen and Tavoyan were forced to construct the Ye-Tavoy railway until 1998, and many escaped brutal labor conditions by heading east to the IDP camps or Thailand. In Mon State that same year, preparations to build the 182-mile Kanbauk to Myaing Kalay gas pipeline that linked Rangoon to the Yadana gas project led to the seizure of more than 2,400 acres of land from villagers and extensive forced labor. In early 2004, a military offensive launched by the Burmese Army in the southern part of Ye Township caused villagers to suffer an array of human rights violations including summary execution, torture, degrading treatment, sexual assault, restricted movement, and forced relocation. Thousands fled to Thailand, convinced that they were still too vulnerable in Halockhani due to its close proximity to army bases.In early 1996, the remaining Mon refugees left Thailand to live in NMSP-administered sites. The MNRC, having changed its name to the Mon Relief and Development Committee (MRDC), continued to facilitate assistance for IDPs in Halockhani, Bee Ree and Tavoy along with other local and international groups. Less than 5% of the total repatriated refugees went back to their native homes, most of them refusing to return due to persistent human rights abuses committed by the military regime. Mon IDPs were promised three years of basic food assistance, after which aid agencies would gradually reduce food aid to encourage self-sufficiency. Nai Kasauh Mon, the director of HURFOM and a former MRDC committee member, explained why this did not happen.“In keeping with the agreement made in 1996 between the Thai government and the NMSP, which stated that IDPs would receive assistance for three years, the rations for IDPs have been reduced since 2000. In addition to financial support, the TBBC provided materials for IDPs to cultivate vegetables and learn farming skills to eventually become independent. However, around 1999 or 2000, TBBC did an assessment of IDP camps and determined that the residents were not yet ready to support themselves due to finite resources spread over a population that kept growing with new arrivals. TBBC decided to continue their support, but with a tapered funding scheme that reduced aid from 12 months per year to 9 months, from 9 months to 7, and from 7 to 5 months. Last year, IDPs received three months of support. Recent reductions also reflect decreased funding, because last year we saw many donors working under the assumption that the fighting had stopped and the IDPs could go home.”Unfortunately, armed clashes and related economic stresses have continued to impact IDP communities. In the wake of the controversial 2010 general elections, conflicts between the Burmese army and Mon ethnic resistance fighters caused another surge in displacement, and UNHCR reported that between 16,000 and 18,000 people sought refuge across the Thai-Burma border that year. In its 2011 report on IDPs, TBBC described the heightened pressure on Mon communities due to scuffles involving Mon breakaway groups, local Burmese authorities, the DKBA, and the backlash after the NMSP refused the government’s request to convert its armed faction into border guard forces.In February of this year, the NMSP renewed its ceasefire agreement with the Myanmar government, and climbing donor support inside Burma and the accolades of regional and international bodies has buoyed confidence in the process. Now that some of the dust has settled over the previous ceasefire failures, people have started to wonder what it might mean to finally go home.

violations including summary execution, torture, degrading treatment, sexual assault, restricted movement, and forced relocation. Thousands fled to Thailand, convinced that they were still too vulnerable in Halockhani due to its close proximity to army bases.In early 1996, the remaining Mon refugees left Thailand to live in NMSP-administered sites. The MNRC, having changed its name to the Mon Relief and Development Committee (MRDC), continued to facilitate assistance for IDPs in Halockhani, Bee Ree and Tavoy along with other local and international groups. Less than 5% of the total repatriated refugees went back to their native homes, most of them refusing to return due to persistent human rights abuses committed by the military regime. Mon IDPs were promised three years of basic food assistance, after which aid agencies would gradually reduce food aid to encourage self-sufficiency. Nai Kasauh Mon, the director of HURFOM and a former MRDC committee member, explained why this did not happen.“In keeping with the agreement made in 1996 between the Thai government and the NMSP, which stated that IDPs would receive assistance for three years, the rations for IDPs have been reduced since 2000. In addition to financial support, the TBBC provided materials for IDPs to cultivate vegetables and learn farming skills to eventually become independent. However, around 1999 or 2000, TBBC did an assessment of IDP camps and determined that the residents were not yet ready to support themselves due to finite resources spread over a population that kept growing with new arrivals. TBBC decided to continue their support, but with a tapered funding scheme that reduced aid from 12 months per year to 9 months, from 9 months to 7, and from 7 to 5 months. Last year, IDPs received three months of support. Recent reductions also reflect decreased funding, because last year we saw many donors working under the assumption that the fighting had stopped and the IDPs could go home.”Unfortunately, armed clashes and related economic stresses have continued to impact IDP communities. In the wake of the controversial 2010 general elections, conflicts between the Burmese army and Mon ethnic resistance fighters caused another surge in displacement, and UNHCR reported that between 16,000 and 18,000 people sought refuge across the Thai-Burma border that year. In its 2011 report on IDPs, TBBC described the heightened pressure on Mon communities due to scuffles involving Mon breakaway groups, local Burmese authorities, the DKBA, and the backlash after the NMSP refused the government’s request to convert its armed faction into border guard forces.In February of this year, the NMSP renewed its ceasefire agreement with the Myanmar government, and climbing donor support inside Burma and the accolades of regional and international bodies has buoyed confidence in the process. Now that some of the dust has settled over the previous ceasefire failures, people have started to wonder what it might mean to finally go home.

IV. Resettlement

Since President Thein Sein took office to lead a nominally civilian government in March 2011, the transformations across Burma’s social and political landscape have captivated local citizens and foreign observers alike. These changes, ranging from slight policy adjustments to administrative overhauls, have altered the way many people look at the country and imagine its future. However, while the international community continues to praise and reward reforms to law, governance, and civil freedoms, people living in Burma have experienced these modifications in widely varying degrees, primarily contingent upon whether they live in urban centers or rural areas along the country’s perimeter.One of the earliest reactions to Burma’s transitions by the international donor community was a shift in funding priorities from the border regions into the country, with organizations responding to the lure of accessing previously isolated populations and the perception that many of the internal threats facing displaced people had diminished. Although service providers at schools, health facilities, and refugee and IDP camps along the Thai border reported being left in the lurch after funding immigrated west, an infectious hope remained that domestic social development programs could mitigate the original drivers of displacement. A natural by-product of this outlook has been the idea that people, not just programs, might be ready to successfully move inside.In January 2012, Burma’s chief peace negotiator and former Railway Minister U Aung Min approached the Norwegian government to request support with the country’s budding peace process and ceasefire agreements. The result was the Myanmar Peace Support Initiative (MPSI), designed to promote peace in conflict-affected areas, reinforce the ceasefire process, and help facilitate the complex and often fragile relationships between the Burmese government, armed ethnic groups, and ethnic communities. The Peace Donor Support Group (PDSG) comprised of Norway, the World Bank, United Nations, United Kingdom, European Union, and Australia was subsequently created to coordinate funding for aid and peace projects in Myanmar, and has reportedly already committed nearly US$500 million.The MPSI funding mandates cover the establishment of liaison offices for non-state armed groups (NSAGs), community-based consultations between NSAGs and ethnic populations, site monitoring of the ceasefire and peace processes, and locally-based needs assessments that can help define what community development projects best suit the various conflict-affected areas. As a result of collaborations with MPSI, eight New Mon State Party (NMSP) liaison offices were opened by July 2012 and consultations have been held in various places along the bor der, but it is the last MPSI goal that directly relates to Mon IDPs.According to Nai Kasauh Mon, the NMSP and MPSI have already begun holding community meetings in IDP sites to gauge support for resettlement programs. Eventually, the NMSP wants to test a “model village” supported by the MPSI in Hnit Kwee village of Yebyu Township, Mon State. The model village will establish a new residency site with a range of services including medical clinics, schools, and land for cultivation. Hnit Kwee is one of ten villages located in the Kim Chaung River area that is currently home to about 6,000 people, many of whom arrived between 1995 and 2000 after fleeing abuses from the Yadana gas pipeline construction. Hnit Kwee village is solely intended to serve IDPs living around Yebyu Township, and the MPSI and NMSP are still identifying appropriate action for people living in IDP sites like Halockhani, Tha-dain, Panan Pone, Jo Haprao, and Palain Japan. It is speculated that these sites may become permanent villages, considering that many residents have lived there for 15 to 30 years and may prefer to remain in the NMSP-controlled areas.Detailed below are a number of resettlement considerations and concerns that were expressed during interviews with members of the Mon IDP population.

der, but it is the last MPSI goal that directly relates to Mon IDPs.According to Nai Kasauh Mon, the NMSP and MPSI have already begun holding community meetings in IDP sites to gauge support for resettlement programs. Eventually, the NMSP wants to test a “model village” supported by the MPSI in Hnit Kwee village of Yebyu Township, Mon State. The model village will establish a new residency site with a range of services including medical clinics, schools, and land for cultivation. Hnit Kwee is one of ten villages located in the Kim Chaung River area that is currently home to about 6,000 people, many of whom arrived between 1995 and 2000 after fleeing abuses from the Yadana gas pipeline construction. Hnit Kwee village is solely intended to serve IDPs living around Yebyu Township, and the MPSI and NMSP are still identifying appropriate action for people living in IDP sites like Halockhani, Tha-dain, Panan Pone, Jo Haprao, and Palain Japan. It is speculated that these sites may become permanent villages, considering that many residents have lived there for 15 to 30 years and may prefer to remain in the NMSP-controlled areas.Detailed below are a number of resettlement considerations and concerns that were expressed during interviews with members of the Mon IDP population.

A. Lack of information

Despite the fact that the MPSI and other relief programs are undoubtedly contemplating how best to coordinate and support communities of displaced people, the current climate surrounding IDP resettlement remains highly sensitive, with agencies and groups carefully keeping the specifics of their deliberations off the record. While organizations may rightly want to avoid publicizing stages of planning that regularly evolve, the hush imposed on the resettlement discussion has served only to open a space for rumors and the circulation of misinformation. The MPSI recently extinguished a publicity fire regarding its perceived ambition to resettle refugees, and the Thai Burma Border Consortium (TBBC) had to allay fears about a rapid repatriation scheme that swiftly spread through border communities. Consequences of inadequate information sharing such as confusion and anxiety were prevalent among the IDPs surveyed for this report. In several cases, the person stated that news of resettlement passed informally between community members or by the village headmen, and there was little evidence that plans for potential relocation were being transmitted directly from the armed group leaders or affiliated NGOs involved with program development. The fact that a buzz has been generated, but without attendant details, has resulted in many IDPs feeling apprehensive about what the impending move could look like or if they are expected to partake.Nai Aung Ko, a laborer in his 40s that fled to Jo Haprao village, said, “I worried when I heard the news that we would have to move to a new place. I am not sure if this is rumor or truth about the resettlement program, but last month, the village chairman told us that we have to move to Hnit Kwee. We, the residents, must consider our jobs and daily survival needs if we really have to relocate. Most people want to move because they hope to receive plots of land from the NMSP to start plantations. If the NMSP or the new place offers enough land, we can cultivate plantations for our livelihoods. But if they give us just enough land to live on, we don’t want to move there because we worry it will be worse than [here]. I was abused by the Burmese military for half my life, so now I want to live with my family in peace.”Nai Ah Bae lives in the Suvanaphom IDP village and summarized the concerns that many displaced people conveyed.

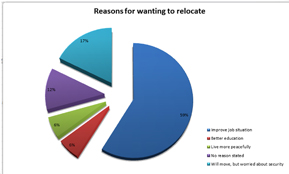

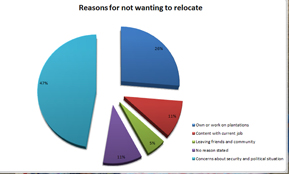

Consequences of inadequate information sharing such as confusion and anxiety were prevalent among the IDPs surveyed for this report. In several cases, the person stated that news of resettlement passed informally between community members or by the village headmen, and there was little evidence that plans for potential relocation were being transmitted directly from the armed group leaders or affiliated NGOs involved with program development. The fact that a buzz has been generated, but without attendant details, has resulted in many IDPs feeling apprehensive about what the impending move could look like or if they are expected to partake.Nai Aung Ko, a laborer in his 40s that fled to Jo Haprao village, said, “I worried when I heard the news that we would have to move to a new place. I am not sure if this is rumor or truth about the resettlement program, but last month, the village chairman told us that we have to move to Hnit Kwee. We, the residents, must consider our jobs and daily survival needs if we really have to relocate. Most people want to move because they hope to receive plots of land from the NMSP to start plantations. If the NMSP or the new place offers enough land, we can cultivate plantations for our livelihoods. But if they give us just enough land to live on, we don’t want to move there because we worry it will be worse than [here]. I was abused by the Burmese military for half my life, so now I want to live with my family in peace.”Nai Ah Bae lives in the Suvanaphom IDP village and summarized the concerns that many displaced people conveyed. “The IDP camp chairman told us that we will move to the new resettlement area with complete security, but we didn’t hear directly from the NMSP leaders about relocating. Where is the new place for resettlement? Will we face difficulty finding jobs, food, and a future there? Is it an area with a lot of disease [malaria]? And is the area near or far from town? We have many things to ask about the new resettlement area because we are worried that the new place could be worse than where we live. We will face another crisis in our lives if there is not enough security because we were already abused and tortured many times by the Burmese military, so much that we fled from our hometown, and we do not want to go and stay in the old area again if it is not safe for us.”Out of 61 IDPs interviewed, the 39 that talked about resettlement were divided almost equally among those who want to relocate (47%) and those that hope to remain where they live now (53%). Notably, almost every interviewee that discussed resettlement used the word “if” to describe their feelings toward relocation, highlighting that even IDPs who look forward to moving, or would consider it, will go only if conditions are met to ensure sufficient employment, food supplies, security, and access to education and healthcare.Mi Myo, a

“The IDP camp chairman told us that we will move to the new resettlement area with complete security, but we didn’t hear directly from the NMSP leaders about relocating. Where is the new place for resettlement? Will we face difficulty finding jobs, food, and a future there? Is it an area with a lot of disease [malaria]? And is the area near or far from town? We have many things to ask about the new resettlement area because we are worried that the new place could be worse than where we live. We will face another crisis in our lives if there is not enough security because we were already abused and tortured many times by the Burmese military, so much that we fled from our hometown, and we do not want to go and stay in the old area again if it is not safe for us.”Out of 61 IDPs interviewed, the 39 that talked about resettlement were divided almost equally among those who want to relocate (47%) and those that hope to remain where they live now (53%). Notably, almost every interviewee that discussed resettlement used the word “if” to describe their feelings toward relocation, highlighting that even IDPs who look forward to moving, or would consider it, will go only if conditions are met to ensure sufficient employment, food supplies, security, and access to education and healthcare.Mi Myo, a 52-year-old resident of Meip Zeip IDP village, worries that if she moves now she will have to start her life all over again.“I will relocate if the land [for cultivation], access to communication, and security situation are good enough to avoid hardship. I want to live and work in a secure area with my children and family, but no one knows yet what problems we may face in the new resettlement area. The situation may be worse, and there is a proverb that says, ‘Sitting is better than standing.’ I am confused about what will happen because I have not heard any news from the organization [MPSI] or NMSP about relocating to the NMSP-controlled area in Tavoy.”The excitement surrounding Burma’s reforms should not eclipse the effects of years of armed conflict, food insecurity,

52-year-old resident of Meip Zeip IDP village, worries that if she moves now she will have to start her life all over again.“I will relocate if the land [for cultivation], access to communication, and security situation are good enough to avoid hardship. I want to live and work in a secure area with my children and family, but no one knows yet what problems we may face in the new resettlement area. The situation may be worse, and there is a proverb that says, ‘Sitting is better than standing.’ I am confused about what will happen because I have not heard any news from the organization [MPSI] or NMSP about relocating to the NMSP-controlled area in Tavoy.”The excitement surrounding Burma’s reforms should not eclipse the effects of years of armed conflict, food insecurity,

joblessness, forced labor, harassment, and fluctuating donor support that the country’s internally displaced population hav

e endured. Resettlement should be treated as a unique opportunity to build trust with IDP communities by ensuring free, prior and informed consent to relocation and prioritizing information sharing and inclusive decision-making. In the wake of previous violence and abuse, di

splaced people were often suddenly confronted with an unknown future and it would be a great misfortune to unnecessarily duplicate that experience now.

B. Security

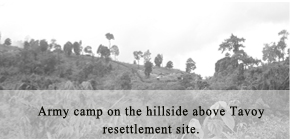

The predominant concern that interviewees expressed regarding relocation was the possibility of renewed fighting in areas outside the current ceasefire zone. People displaced by war or military abuses revealed a clear correlation between the uneasiness they felt toward resettlement and past encounters with conflict. Over half of the IDPs that reported being opposed to relocation cited fear of inadequate safety measures, including doubts about Burma’s changing political situation and suspicion that resettlement areas would not be as peaceful as their current villages or camps.The lingering distrust of the Burmese military was apparent in a number of interviews conducted with IDPs. Nai Sein Min, 63, who fled his hometown in 1978 and eventually arrived at Chedeik IDP village in 2000, said, “I left my village because I could not stand the indiscriminate torture by the Burmese military during the term of General Ne Win. We hear that transportation and the [freedom to] travel have improved under the transitional government, but we know nothing about politics in our community because we are in the jungle. If we go back inside Burma, [Mon people] will gradually be killed off because the military still keeps to its old policies.”Mi Dot, a mother of five from Tenasserim Region, agreed with Nai Sein Min’s assessment, saying, “I left my hometown in 1990 and got to Halockhani in 1995. Since my husband knew people in the NMSP, the [Burmese] military accused him of being linked with the Mon rebel group [and of supporting them during] the four cuts campaign. The military confiscated the rice fields in Day Thoung and Salar Dha Kaw, forced us to porter, and tortured us increasingly. Because of this, I fled to Three Pagodas Pass and passed through Poud Ju area to get to Halockhani camp. Even if there is a new place in the ceasefire area, I do not want to relocate because one day the military will torture and abuse us again and here it is more peaceful.”Nai Blain Doot, 45, is originally from Pauk Pin Kwin, one of the villages in Yebyu Township that suffered decades of consecutive violations by the SLORC, the SPDC, and local authorities involved with the Yadana gas project. As a result of the gas pipeline construction, Pauk Pin Kwin endured forced labor, intensified security presence, mobility restrictions, widespread displacement, and loss of livelihood caused by broad swathes of land confiscation. After escaping the hardships in Pauk Pin Kwin, Nai Blain Doot moved to Baleh Done Phai IDP site only to witness continued brutality.“We have lived in this village since 1993. At that time, Baleh Done Phai resettlement site was quite new. In the second week of July 1994, the site was burned to the ground because Burmese Infantry Battalion (IB) No. 62 wanted to stop villagers from supporting the MNLA. Thousands of Mon families fled into Thailand to take refuge, but we were all forced to return a few weeks later. The IB No. 62 burned down this site just one year before the New Mon State Party and the SLORC signed a ceasefire agreement in Moulmein. So, the fact that local authorities are planning to resettle the IDPs is fine, but we would like to see that the new place not only offers ways for us survive, but also secure conditions. For me, I don’t want to experience another 1994 again.”Nai Kyaw Tu has lived in Panan Pone village since 1998 and is not yet convinced that the new government can promise or deliver a stable environment. “According to the Kachin Independent Organization’s Burmese news, there is still civil war in our country because the government and ethnic groups continue to fight. Even though the American president Barack Obama could withdraw the US military from Iraq, the Burmese President U Thein Sein cannot withdraw the military from Kachin State. President Thein Sein is not able to stop the hostility in Kachin State. We can see this happening [despite] the new government’s reform in the country. We do not want to move to the new site because this area is very peaceful and has been familiar to us for a long time.”The interview with 67-year-old Jo Haprao resident Nai Kmean Aie demonstrated a perspective from the elderly IDP community, for which relocation may pose unique challenges. “Even if there is a new place for us, I will not go there because I am much older now and my eyes don’t see so well. I just spend my life here helping, encouraging, and giving suggestions [to others] even though I cannot physically contribute like in the past. Also, this is a peaceful place where we can do what we want. If we can work, earn, store rations, and move around freely here, we will feel that there is improvement.”The situation for women IDPs contemplating relocation also deserves special attention. The former military regime was frequently criticized for using rape as a systematic weapon of war, and many local Mon women from the conflict zones of Ye and Yebyu Townships withstood sexual assault and intimidation that drove hundreds of families from their homes. Two of the displaced Mon women surveyed were assaulted by the Burmese Army Infantry, but preferred not to disclose the details of their stories. Instances of sexual violence against women have also been chronicled in IDP sites, where women walking home alone or working in plantations before sunrise have reported rape or sexual advances.In addition to sexual abuse, women living in IDP sites may have endured unfair employment practices, lower wages than their male counterparts, and heightened responsibility to provide for families after husbands or sons leave due to conflict or migrant work. A few women IDPs started their own local businesses, but most are at the mercy of sporadic income from seasonal work digging for bamboo shoots, working in orchards or rubber plantations, and cutting long grass to make brooms. One 40-year-old woman in Halockhani camp interviewed earlier this year said, “I divorced my husband over two years ago and I need to care for and feed my children, who attend school while I try to find work. In [the camp] many people work on the farm, but farm owners do not hire female laborers because they think women cannot work as hard as men. The male workers get paid 150 Baht per day, and women should be able to work the same job for the same salary. It is very difficult for women who do not have a husband to get a job on the farm. If we could just get enough rice, I think we would not face such difficulties. Many women work hard and still only have enough money to buy food, nothing extra.”Although many women face daily challenges in IDP sites, this did not automatically translate into a desire to leave. Of the 24 women IDPs interviewed, the 18 that discussed relocation were split down the middle between wanting to move (9) and preferring to stay (9). The majority of women IDPs that expressed interest in moving cited better job opportunities (7) as the primary appeal.Women reported anxiety towards resettlement for a variety of reasons, though primarily related to finding jobs or places to live, or their lack of trust that the government would help them resettle.Mi Ei May, 59, said, “I was one of the homeless [displaced] people among 300 households in Kyauktayan village. Most villagers had nothing left. Some men were shot and killed where they stood by the Burmese troops without any interrogation. My husband, four of my children and I ran from the incident alongside other [villagers] to seek refuge in the New Mon State Party area. Later, we decided to live in this Meip Zeip resettlement site, operated by the NMSP. Now, we have a plantation, but we heard that the New Mon State Party is planning a new resettlement program. As for me, I don’t want to move from this location because this is where my husband died and I want to live here for the rest of my life.”Social and legal systems that tolerated the gender discrimination and sexual abuse endured by women IDPs, either in the lead up to their displacement or in their current resettlement sites, must not be reproduced in new locations. The resettlement process is likely to succeed only if protection and security precautions are applied uniformly across the varied demographics of displaced people. Faith in the government may slowly be restored with further good faith measures, and steering the ongoing dialogues with ethnic groups toward more permanent political peace agreements is a key factor. Confidence can also be built through the government’s approval and enforcement of de-militarized zones around resettlement sites that withdraw troops to an agreed-upon distance, along with demonstrated commitment to demining activities. The Myanmar country profile released this September by the Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor reported that six townships in Mon state suffer from some degree of mine contamination, constituting a serious threat to be addressed prior to any meaningful resettlement plan.Nai Taung Aye from Jo Haprao IDP vill

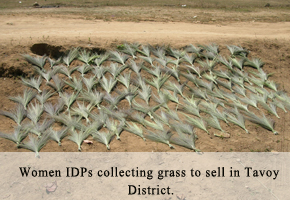

“According to the Kachin Independent Organization’s Burmese news, there is still civil war in our country because the government and ethnic groups continue to fight. Even though the American president Barack Obama could withdraw the US military from Iraq, the Burmese President U Thein Sein cannot withdraw the military from Kachin State. President Thein Sein is not able to stop the hostility in Kachin State. We can see this happening [despite] the new government’s reform in the country. We do not want to move to the new site because this area is very peaceful and has been familiar to us for a long time.”The interview with 67-year-old Jo Haprao resident Nai Kmean Aie demonstrated a perspective from the elderly IDP community, for which relocation may pose unique challenges. “Even if there is a new place for us, I will not go there because I am much older now and my eyes don’t see so well. I just spend my life here helping, encouraging, and giving suggestions [to others] even though I cannot physically contribute like in the past. Also, this is a peaceful place where we can do what we want. If we can work, earn, store rations, and move around freely here, we will feel that there is improvement.”The situation for women IDPs contemplating relocation also deserves special attention. The former military regime was frequently criticized for using rape as a systematic weapon of war, and many local Mon women from the conflict zones of Ye and Yebyu Townships withstood sexual assault and intimidation that drove hundreds of families from their homes. Two of the displaced Mon women surveyed were assaulted by the Burmese Army Infantry, but preferred not to disclose the details of their stories. Instances of sexual violence against women have also been chronicled in IDP sites, where women walking home alone or working in plantations before sunrise have reported rape or sexual advances.In addition to sexual abuse, women living in IDP sites may have endured unfair employment practices, lower wages than their male counterparts, and heightened responsibility to provide for families after husbands or sons leave due to conflict or migrant work. A few women IDPs started their own local businesses, but most are at the mercy of sporadic income from seasonal work digging for bamboo shoots, working in orchards or rubber plantations, and cutting long grass to make brooms. One 40-year-old woman in Halockhani camp interviewed earlier this year said, “I divorced my husband over two years ago and I need to care for and feed my children, who attend school while I try to find work. In [the camp] many people work on the farm, but farm owners do not hire female laborers because they think women cannot work as hard as men. The male workers get paid 150 Baht per day, and women should be able to work the same job for the same salary. It is very difficult for women who do not have a husband to get a job on the farm. If we could just get enough rice, I think we would not face such difficulties. Many women work hard and still only have enough money to buy food, nothing extra.”Although many women face daily challenges in IDP sites, this did not automatically translate into a desire to leave. Of the 24 women IDPs interviewed, the 18 that discussed relocation were split down the middle between wanting to move (9) and preferring to stay (9). The majority of women IDPs that expressed interest in moving cited better job opportunities (7) as the primary appeal.Women reported anxiety towards resettlement for a variety of reasons, though primarily related to finding jobs or places to live, or their lack of trust that the government would help them resettle.Mi Ei May, 59, said, “I was one of the homeless [displaced] people among 300 households in Kyauktayan village. Most villagers had nothing left. Some men were shot and killed where they stood by the Burmese troops without any interrogation. My husband, four of my children and I ran from the incident alongside other [villagers] to seek refuge in the New Mon State Party area. Later, we decided to live in this Meip Zeip resettlement site, operated by the NMSP. Now, we have a plantation, but we heard that the New Mon State Party is planning a new resettlement program. As for me, I don’t want to move from this location because this is where my husband died and I want to live here for the rest of my life.”Social and legal systems that tolerated the gender discrimination and sexual abuse endured by women IDPs, either in the lead up to their displacement or in their current resettlement sites, must not be reproduced in new locations. The resettlement process is likely to succeed only if protection and security precautions are applied uniformly across the varied demographics of displaced people. Faith in the government may slowly be restored with further good faith measures, and steering the ongoing dialogues with ethnic groups toward more permanent political peace agreements is a key factor. Confidence can also be built through the government’s approval and enforcement of de-militarized zones around resettlement sites that withdraw troops to an agreed-upon distance, along with demonstrated commitment to demining activities. The Myanmar country profile released this September by the Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor reported that six townships in Mon state suffer from some degree of mine contamination, constituting a serious threat to be addressed prior to any meaningful resettlement plan.Nai Taung Aye from Jo Haprao IDP vill age said, “Regarding changes, the [Burmese] military welcomed the Mon revolution group to join the ceasefire and be involved in elections. There are some new developments happening, and the government is allowing big companies to do foreign investment and support funding for ethnic education. However, the military is still following the same rule of law, and the power is still in their hands. I heard about relocating to a new place but I do not know where it is. I will relocate if I can do good business there. However, since I am a soldier, I have not had a chance yet to do as I wish. In this village, nothing has changed, but there will be changes in the future according to our leader.”

age said, “Regarding changes, the [Burmese] military welcomed the Mon revolution group to join the ceasefire and be involved in elections. There are some new developments happening, and the government is allowing big companies to do foreign investment and support funding for ethnic education. However, the military is still following the same rule of law, and the power is still in their hands. I heard about relocating to a new place but I do not know where it is. I will relocate if I can do good business there. However, since I am a soldier, I have not had a chance yet to do as I wish. In this village, nothing has changed, but there will be changes in the future according to our leader.”

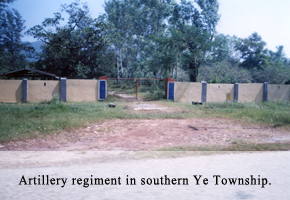

C. Jobs and Land

For many families in Burma, land is essential to their jobs, homes, and food security. The fundamental role that cultivation plays is written on the country’s landscape with multicolored strokes of interlacing betel nut and rubber plantations, groves of tropical fruit trees, and gently terraced rice paddies. In August, a Thompson Reuters special report[4] stated that seventy percent of Burma’s 60 million people live on farms, and land’s central function in the lives of IDPs appeared frequently in HURFOM’s collected testimonies. The strong bond between people and their environments helps to explain some reluctance toward relocation and the deep distrust for government institutions that formerly took their land away.Originally from Lein Maw Chan in Ye township, 56-year old Nai Gro now lives with his family in Kyai Soi Mon IDP resettlement site near Halockhani camp.“I came here after authorities seized my 13-acre rubber plantation to use for the Ye Township artillery regiment construction in 2004. At that time, Burmese authorities confiscated approximately 550 acres of agricultural land, including my 13 acres. My family, along with my father’s family, planted 3,800 rubber trees on our land. When the Burmese battalion No. 317 ordered our land to be confiscated, we tried to appeal to the Moulmein-based Southeast Command leaders. The plan didn’t work, and a few months later all 22 farming families on the 550 acres lost their plantations

. We did not get any compensation from the authorities. Without our land or income, my family started going into debt, and in the end of 2004 all eight members of the family left our village and decided to resettle in this camp. Some families that lost their land felt like me, leaving their native homes without any hope, and traveling to the Thai-Burma border to start new lives.”Today, years after their original resettlement, many Mon IDPs still have jobs that are inextricably tied to the land. Families earn money by cutting and transporting wood, collecting bamboo shoots, growing and selling vegetables, hunting, or working on farms and paddy fields. Day laborers often combine short-term jobs like clearing grass on plantations, carrying materials for local business owners, and offering roadside cooking for travelers to meet their monthly living expenses.Employment can be intermittent or severely curtailed by the four-month rainy season when ferry captains, truck drivers, and pedestrian guides to Thailand are unable to work. Nai Myit helps shuttle goods downriver and said, “If I do a good job assisting the boat owner, I can earn 10,000 kyat for each trip. But it is dangerous work, especially in the rain. This past July 8, my friend was killed when his boat overturned in a strong current. I say this because sometimes the benefits we receive do not equal what we may have to pay back.”

. We did not get any compensation from the authorities. Without our land or income, my family started going into debt, and in the end of 2004 all eight members of the family left our village and decided to resettle in this camp. Some families that lost their land felt like me, leaving their native homes without any hope, and traveling to the Thai-Burma border to start new lives.”Today, years after their original resettlement, many Mon IDPs still have jobs that are inextricably tied to the land. Families earn money by cutting and transporting wood, collecting bamboo shoots, growing and selling vegetables, hunting, or working on farms and paddy fields. Day laborers often combine short-term jobs like clearing grass on plantations, carrying materials for local business owners, and offering roadside cooking for travelers to meet their monthly living expenses.Employment can be intermittent or severely curtailed by the four-month rainy season when ferry captains, truck drivers, and pedestrian guides to Thailand are unable to work. Nai Myit helps shuttle goods downriver and said, “If I do a good job assisting the boat owner, I can earn 10,000 kyat for each trip. But it is dangerous work, especially in the rain. This past July 8, my friend was killed when his boat overturned in a strong current. I say this because sometimes the benefits we receive do not equal what we may have to pay back.”

The motorway from Ye Township in Mon State to Three Pagodas Pass on the Thai-Burma border has become a popular source of seasonal income for IDP communities running along its path. Residents of Halockhani and Baleh Done Phai camps transport a variety of materials before the rainy season turns the passage to mud, though drivers assert that the deeply cratered road bounces cars off the side in summer as well. Chedeik village residents report earning 200 kyat for every 1.6 kilos they can carry on their backs along the motorway, typically hoisting between 30 and 45 kilos per trip. Locals also accompany travelers from Ye to the Thai border, a four-day journey that pays 30,000 to 40,000 kyat.In these cases, income is derived directly from displaced people’s immediate surroundings, making a move from their current environment to an unknown location look incredibly risky. Additionally, some people that succeeded in securing stable or semi-stable jobs after years of erratic income flows may be apprehensive about starting the process again in unfamiliar territory. In the interviews taken for this report, IDPs opting to relocate and those hoping to permanently remain in their current locations both quoted “jobs” as a key influence on their decisions. Individuals and families with a relatively consistent income source are concerned about losing it, and those struggling to make ends meet are eager to try their luck elsewhere.”We did not get word telling us to move to a new place, but we would like to move somewhere that offers more work opportunities. In the [resettlement] area, if there is more work available for us and the situation is still quiet and peaceful, we would like to relocate there,” said Mi Choe Win, a 33-year old resident of Halockhani camp.Nai Oung Myit, 45, from Burk Surk village said, “I heard the new place where we have to relocate is around the area of Top of Kin River or Yapu or I am not sure, however, I want to go to the new place if I can do good business there. The village where I live now is small, there are only around 20 households.”Nai Mon Aye and Mi Ngay Kyii are pleased with thei

The motorway from Ye Township in Mon State to Three Pagodas Pass on the Thai-Burma border has become a popular source of seasonal income for IDP communities running along its path. Residents of Halockhani and Baleh Done Phai camps transport a variety of materials before the rainy season turns the passage to mud, though drivers assert that the deeply cratered road bounces cars off the side in summer as well. Chedeik village residents report earning 200 kyat for every 1.6 kilos they can carry on their backs along the motorway, typically hoisting between 30 and 45 kilos per trip. Locals also accompany travelers from Ye to the Thai border, a four-day journey that pays 30,000 to 40,000 kyat.In these cases, income is derived directly from displaced people’s immediate surroundings, making a move from their current environment to an unknown location look incredibly risky. Additionally, some people that succeeded in securing stable or semi-stable jobs after years of erratic income flows may be apprehensive about starting the process again in unfamiliar territory. In the interviews taken for this report, IDPs opting to relocate and those hoping to permanently remain in their current locations both quoted “jobs” as a key influence on their decisions. Individuals and families with a relatively consistent income source are concerned about losing it, and those struggling to make ends meet are eager to try their luck elsewhere.”We did not get word telling us to move to a new place, but we would like to move somewhere that offers more work opportunities. In the [resettlement] area, if there is more work available for us and the situation is still quiet and peaceful, we would like to relocate there,” said Mi Choe Win, a 33-year old resident of Halockhani camp.Nai Oung Myit, 45, from Burk Surk village said, “I heard the new place where we have to relocate is around the area of Top of Kin River or Yapu or I am not sure, however, I want to go to the new place if I can do good business there. The village where I live now is small, there are only around 20 households.”Nai Mon Aye and Mi Ngay Kyii are pleased with thei r work clearing brush from rubber plantations and worry about starting a new life.”Arriving in a new place means taking a lot of time to create a stable situation. When we have work here, my wife earns 3,000 kyat and I earn 5,000, so we can earn 8,000 kyat in one day. Sometimes, we have to dig holes to plant rubber tree saplings when we get jobs on a new plantation. It is tiring work for us, but we can get regular income this way. There may be many new things for us to learn about and endure if we relocate. We do not know if the new place will be comfortable for our family to live, and we may need time to solve these problems. Also, we cannot live there without work, even if it is peaceful. In the past, just my income alone paid our food costs, but now both my wife and I have to work to cover the family expenses, so work is very important to us.”

r work clearing brush from rubber plantations and worry about starting a new life.”Arriving in a new place means taking a lot of time to create a stable situation. When we have work here, my wife earns 3,000 kyat and I earn 5,000, so we can earn 8,000 kyat in one day. Sometimes, we have to dig holes to plant rubber tree saplings when we get jobs on a new plantation. It is tiring work for us, but we can get regular income this way. There may be many new things for us to learn about and endure if we relocate. We do not know if the new place will be comfortable for our family to live, and we may need time to solve these problems. Also, we cannot live there without work, even if it is peaceful. In the past, just my income alone paid our food costs, but now both my wife and I have to work to cover the family expenses, so work is very important to us.”

D. Education and Health

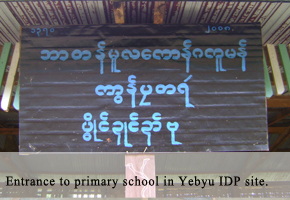

The value traditionally placed on education in Mon culture is well documented and needs little introduction here, other than to state that it was faithfully articulated in many IDP interviews. Although only 29 out of the 61 interviewees addressed the subject of education, of those, quite a few chose it as their sole topic of conversation. Interviewees discussed the importance of education to resettlement considerations, but also noted the visible changes in schooling costs in their communities, another reflection of the shifting funding priorities by service providers along the border. Residents of Baleh Done Phai camp remembered when each of the 150 households paid 540 kyat per month for school costs, and claim the price has now risen to 10,800 kyat per household. Several IDPs commented on their willingness to contribute to school funding and teachers’ salaries to support the advancement of younger generations, and while few deemed education costs to be unreasonably high, some described that they become burdensome when income is erratic or sparse.Baleh Done Phai resident Nai Win Naing said, “Our family has a hard time providing education support because we have a small income. This is not because we are lazy to work, it is because of the lack of jobs. Mon people are willing to donate to education when we have enough money, but now our extra income only covers our food. Our family does not have many children going to school, but 10,800 kyat per month is really difficult for us.”Nai Than Swea has lived in Halockhani camp for eight years and explained the close relationship between income and education. “The job situation here is directly linked to the reason why households cannot afford education. In the past, we didn’t worry because we could find bamboo shoots nearby and sell them. Now, we have to walk for more than three hours to find bamboo shoots. So many more people are doing this for a job, and the bamboo shoots are almost nonexistent. Without this work, it’s hard getting money for food, and we feel sad that we are poor and not able to support our children’s education.”In many IDP areas, particularly Halockhani and Baleh Done Phai, students may stop attending classes after they reach the highest grade available at their local school, which is typically fifth or sixth grade. After that, the journey to reach middle school or one of the two Mon high schools in NMSP-controlled areas may be too arduous, too expensive, or too great a loss to the family income to relinquish the extra wages the young person can earn. Students that live far from school can choose to live in dormitories in Nyi Sar, but requisite fees climb to around 100,000 kyat per year.Rubber plantation worker Nai Kyaw Tu, 42, lives in Panan Pone village of the Bee Ree IDP area and said, “We want to promote better education for our children. We need to open a middle school in our village because we cannot afford to support our children to go the school in Nyi Sar. Most students just stop going school.”Mi E’ Bae currently lives with her husband in Chedeik village and advocated strongly for a no-cost education option for low-income families.

“The job situation here is directly linked to the reason why households cannot afford education. In the past, we didn’t worry because we could find bamboo shoots nearby and sell them. Now, we have to walk for more than three hours to find bamboo shoots. So many more people are doing this for a job, and the bamboo shoots are almost nonexistent. Without this work, it’s hard getting money for food, and we feel sad that we are poor and not able to support our children’s education.”In many IDP areas, particularly Halockhani and Baleh Done Phai, students may stop attending classes after they reach the highest grade available at their local school, which is typically fifth or sixth grade. After that, the journey to reach middle school or one of the two Mon high schools in NMSP-controlled areas may be too arduous, too expensive, or too great a loss to the family income to relinquish the extra wages the young person can earn. Students that live far from school can choose to live in dormitories in Nyi Sar, but requisite fees climb to around 100,000 kyat per year.Rubber plantation worker Nai Kyaw Tu, 42, lives in Panan Pone village of the Bee Ree IDP area and said, “We want to promote better education for our children. We need to open a middle school in our village because we cannot afford to support our children to go the school in Nyi Sar. Most students just stop going school.”Mi E’ Bae currently lives with her husband in Chedeik village and advocated strongly for a no-cost education option for low-income families. “Before, our children received assistance with pens, pencils, and exercise books from the NMSP and MNEC. Now, we cannot afford to pay much for our children’s expenses because we are a poor family. If we work one day, we can buy our food for one day. I do not want this kind of education system. Of my four children, one goes to school, two stopped going, and the youngest is not yet school age. If this system continues, a poor family like us can’t afford their children to attend school for long.”Along with the buzz circulating about resettlement programs, rumors that the Mon National Education Committee (MNEC) is expecting a much-needed boost in funding have pleased many IDP site residents.Mi Pone Non lives with her three children in Panan Pone and remarked, “Some donors came and met with the Mon National Education Committee this month in order to promote better education for our village. In 2006, our village school had kindergarten to sixth grade. Now, they decreased it to fifth grade. Sixth and seventh grade students have to walk to Nyi Sar and some students dropped out because of high costs this year.”

“Before, our children received assistance with pens, pencils, and exercise books from the NMSP and MNEC. Now, we cannot afford to pay much for our children’s expenses because we are a poor family. If we work one day, we can buy our food for one day. I do not want this kind of education system. Of my four children, one goes to school, two stopped going, and the youngest is not yet school age. If this system continues, a poor family like us can’t afford their children to attend school for long.”Along with the buzz circulating about resettlement programs, rumors that the Mon National Education Committee (MNEC) is expecting a much-needed boost in funding have pleased many IDP site residents.Mi Pone Non lives with her three children in Panan Pone and remarked, “Some donors came and met with the Mon National Education Committee this month in order to promote better education for our village. In 2006, our village school had kindergarten to sixth grade. Now, they decreased it to fifth grade. Sixth and seventh grade students have to walk to Nyi Sar and some students dropped out because of high costs this year.” A 22-year old Mon schoolteacher and resident of Jo Haprao IDP village described how a friend alerted her to the significant backing that Mon schools would soon acquire, and explained the timeliness of a funding increase. In her experience, parents never wanted to take their children out of school, but perceived the move to be an unfortunate matter of necessity. Most families in Jo Haprao cut wood, grow betel nut, or sell vegetables, but there is not enough land to provide work for everyone. She said that rations from the MRDC used to cover income gaps, but now the aid has stopped, and families that were barely keeping afloat are visibly struggling.“The books are cheap to buy, but it’s the school clothes that parents have difficulty affording. Also, young people who are in school cannot lend a hand around the house or earn extra income, and families separated by migrant work or displacement may not be able to survive without this added help. In Jo Haprao, students were required to pay 2,500 kyat at the beginning of each school year, and every household in the village paid 1,500 kyat per month to contribute to teachers’ salaries. People were happy to support education, but there were times that families could not afford the cost. If they missed one month, they had to pay double the next, and might borrow from a local shop or wealthy family, with interest, to avoid missing a payment. There are microcredit lenders, but families borrow and then can’t pay the loan back. This could lead to children being pulled from school, and debt drove many family members to pursue migrant work in Thailand. When I taught at Jo Haprao a few years ago, some of the 14-year olds would suddenly leave for Thailand, or the young ones would have to go with parents emigrating for work. If new funding is coming for our Mon schools, it will help to prevent these kinds of problems.”In many Mon IDP areas, parent-teacher associations are tasked with collecting money from the community to support teachers’ salaries and education costs. These obligatory contributions double the salaries Mon teachers would otherwise receive from the Mon National Education Committee, which pays them between 20,000 and 25,000 kyat per month. Mi Moe, a member of the parent-teacher association in Panan Pone village, said, “I collect money from students’ parents every month and it is a hard job. I myself witness that the parents have really low incomes and no stable work, so it is tough for them to even cover their daily food costs. But if our association could not afford to pay 40,000 kyat [for salaries], no teacher would come teach in our village. Since the teacher might leave and go somewhere else, we sometimes borrow money from lenders and then can only pay back the loans after students’ parents pay us.”Jo Haprao village resident Nai Maung O’ gets occasional work ferrying logs downriver to Ye Township. He captured the sentiment shared by many IDPs that if he had a reliable income, he would be willing to support education.”We are poor and were harassed by the military, so we did not go to school. If we could get regular work, we would be glad to fund our children’s schooling, but we don’t, so we worry. I transport logs with other workers from our village; each trip takes three days and pays us 10,000 kyat. However, this job is sporadic and the money mostly covers our food costs. We can spend on our children’s schooling and healthcare only if there is extra. We will have to move if the NMSP relocates us, though I worry that we will not have a safe situation if the NMSP and military fight again.”